COVID-19 has resolved our most popular client question of the last five years – “when will this cycle end?’ Even as the number of infections slows and the lockdowns end, most economies will reopen to a serious global recession, including high unemployment and a deteriorating credit cycle. Naturally, the focus has now switched to the likely strength and speed of the economic recovery. Yet, some investors are looking further ahead, wondering how the ‘fundamentals’ of the global economy might change once the pandemic is over. In many ways, the 2010s expansion was remarkable. Not only was it the longest period of unbroken growth in history, it was also the most sluggish. It seemed the global economy was only capable of short, temporary bursts of ‘reflation’, a series of mini stop-go cycles. Though the long expansion eventually dragged unemployment down to multi-decade lows, in other ways the cycle never really “got going”. Wages and inflation stayed subdued, which kept central banks in a relentless battle with the lower policy bound. Only the Federal Reserve managed to raise interest rates meaningfully, which only exacerbated the deflationary problems elsewhere (the dollar shortage). The 2010s was a buoyant time for markets, but also an era of rising inequality, polarization and populism.

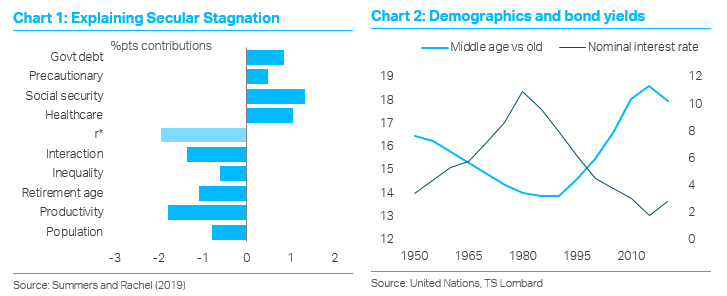

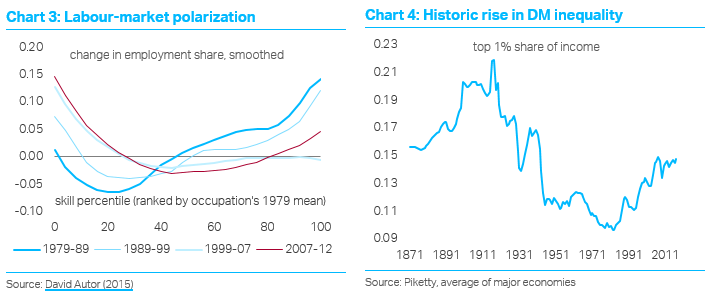

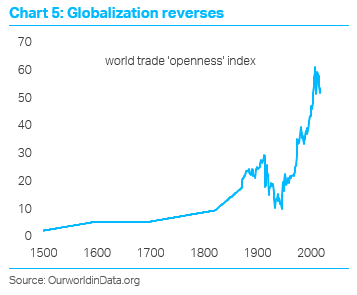

A bad policy mix (loose monetary, excessively tight fiscal) has surely exacerbated this “New Mediocre”. The world’s increasing sensitivity to China’s domestic stimulus – something that surprised most investors in the 2010s – suggests the more aggressive use of DM balance sheets would have been a more meaningful way to generate sustained ‘reflation’ (consistent with the swelling academic literature on Secular Stagnation). Yet, policymakers also had to overcome three powerful secular forces – Demographics, Globalization and new Technologies. While none of these deflationary trends were specifically new to the 2010s, they clearly played a role in shaping the underlying macroeconomics of the New Mediocre. In combination, the Big Three: (i) raised the world’s desired saving rate (lowering equilibrium interest rates), (ii) further undermined workers’ bargaining power (reducing the average wage share), and; (iii) caused an additional flattening in the Phillips curve, which thwarted the authorities attempts to ‘rebalance’ and reflate their economies by reducing unemployment. The combination of technology and globalization had a particularly powerful impact on labour markets, destroying the middle of the income distribution – workers either had to ‘skill-up’ or take low wage service-sector jobs. Worryingly, technological diffusion also slowed, encouraging the dominance of new ‘superstar’ firms.

So what might change in the 2020s? Breaking out of the New Mediocre will not be easy, especially as the long search for yield in financial markets, rising corporate debt levels and widening inequality have created durable ‘hysteresis’ effects. COVID-19 has added further complications, potentially exaggerating Secular Stagnation. Private-sector savings have already increased. We are hopeful about the policy mix, since the authorities now seem to understand that fiscal stimulus must take over from ineffective monetary instruments, though we can’t rule out premature budget tightening and 2010-style fiscal errors. Meanwhile, two of the Big Three secular forces that shaped the New Mediocre are set to unwind, which in principle should ease the structural deflation story. The mass ranks of the middle aged will hit retirement age, which should curb their saving rates. And globalization, which had stalled even before COVID-19, will give way to De-globalization. Figuring out what happens in the technology sector is trickier, as it depends on future innovations, the behaviour of the big tech companies and the public policy response. But the next cycle will surely provide a more challenging environment for markets. Equilibrium interest rates could rise, the profit share could decline and the relationship between bonds and equities could shift. The continuous rerating of all asset classes could be over.

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact