Every economist wants to be famous for some great idea they had or to have their name forever linked to an original economic concept or unique thought. We have Keynesian demand-management, Friedman’s monetarism, Goodhart’s law and even the Sahm rule. In my case, however, this career objective has not gone as I once hoped. To the extent anyone in the profession recognizes my name, it is synonymous with once owning a gold BMW or my take-down of sell-side economics (sadly, the most popular thing I have ever written). Whenever a TS Lombard competitor claims there is a 40% chance of nuclear Armageddon, or estimates a 0.3% hit to euro-area GDP from oil prices reaching $500 per barrel, I get 300 notifications on Twitter recognizing that this is one of my “sell-side rules” in action. But I have not given up. My latest idea is possibly my best ever (yes, low benchmark....) even though it bears the name of another Italian with equally impressive style and charisma: the “Paolo Maldini guide to central banking”. The idea is simple: once inflation is a problem, there is no real chance of a “soft landing” because the central bank has already messed up. And today, unfortunately, the prospect of a soft landing seems to be fading.

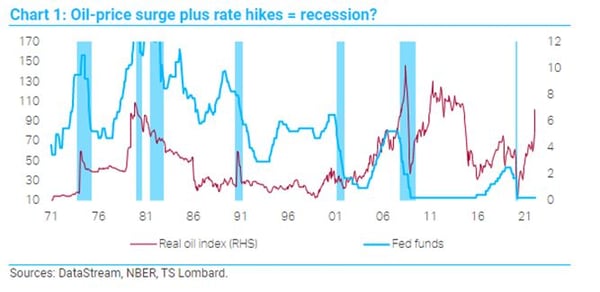

Let me explain. Paolo Maldini was a legendary Italian football player, a defender who – at least at club level – won pretty much everything in the game. When asked about his approach to defending, he famously responded: “If I have to make a tackle, I have already made a mistake”. By which he meant that defending was mostly about positioning and timing, not physically taking the ball away from the opponent. And the same applies to monetary policy. Central banks have been most successful when they have anticipated inflation and put themselves in a position to prevent it. Once the economy is already overheating and inflation has become a problem, the only option they have left is to make a late, last-ditch attempt to force it lower. There were no soft landings in the 1970s and 1980s. Central banks had only one option to get inflation under control – force unemployment higher by jacking up interest rates enough to cause a recession. Paul Volcker’s approach was effective but certainly lacked the sophistication of the silky Italian. (It was closer to the Marco Materazzi School of defending – you remember him: the uncompromising defender who insulted Zinedine Zidane’s family honour in the 2006 World Cup final.)

Why does this matter? If the current episode of inflation proves to be “transitory”, it will not matter at all. And we continue to believe global CPIs will eventually drop to levels central banks are willing to tolerate even without them having to jack up interest rates to extreme contractionary levels. Inflation probably will not return to the low levels we had before COVID, but it may settle only moderately above central banks’ targets. An annual increase of 2-3% in the CPI would be ideal, but even a 3-4% rise would be tolerable given the experience of the past two years. Central banks would never admit they were happy with a continuous “overshoot” – they would remain hawkish, probably even raising interest rates above the bond market’s current terminal rate – but they would not become sufficiently agitated about this situation to adopt a more aggressive inflation-fighting strategy. If, right now, you offered them an economy at full employment in 2023 with inflation at 3.5%, they would probably bite your hand off (not to be confused with the “Luis Suarez approach to monetary policy”, a footballer famous for several episodes in which he was caught biting opposition players).

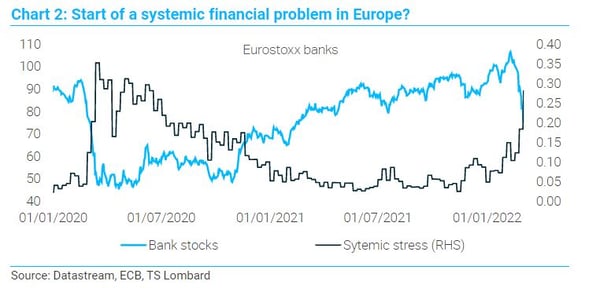

The situation in Ukraine, of course, is putting central banks in an increasingly difficult situation. Energy and food prices are spiralling higher, while near-term growth prospects are looking bleaker – especially in Europe, which is most exposed across both dimensions. Conditions in European credit markets are deteriorating, too, as investors try to figure out what Russia’s separation from the rest of the world means for financial stability in the region. And last night Zoltan Poszar warned about potential contagion from global commodity markets to the rest of the financial sector. While even the increasingly hyperbolic Zoltan does not think Russia is a “Lehman moment” for the global economy, it is large enough to create significant spillovers; and it will be a while before we know specifically where those exposures lie. In the meantime, counterparty uncertainty has increased and market liquidity has evaporated. Central banks are caught between worrying about the near-term risks to the financial sector (which are not yet clear) and their fear that, by keeping policy exceptionally loose in the face of high inflation, they are repeating the mistakes their predecessors made in the 1970s. There are, after all, some eerie similarities right now.

Even if there is a resolution in Ukraine, there is huge uncertainty about where inflation eventually settles, which means the odds of a “soft landing” are not good. To see why, we can use Alan Blinder’s recent guide to US tightening cycles. (Alan Blinder was vice-president to Alan Greenspan in the mid-1990s.) Blinder showed, alarmingly, that the Fed achieved the textbook soft landing only in two of its previous 11 tightening cycles (in 1966 and 1994). On both occasions, the US experienced an economic slowdown but did not suffer a serious contraction in GDP or a rise in unemployment. These results are not encouraging, particularly when we recognize that inflation was relatively well behaved during both periods. In fact, when we look at Blinder’s analysis in detail, we can see that there have been three types of tightening cycle since the 1960s. The first two happen when inflation is low; here, either the Fed is able to generate a soft landing or, more often, low interest rates inflate a financial bubble that eventually bursts (which causes a recession anyway). But the third type of tightening cycle is the one that investors should worry about. It happens when inflation is already a problem and the central bank has no choice but to generate a recession to force the CPI onto a lower trajectory. By design, these episodes never end in a soft landing.

Put another way, even if we avoid a financial accident from what is happening in Ukraine, but the inflation problem turns out not to be “transitory” – instead remaining above the levels central banks are prepared to tolerate – the chance of a soft landing would be around ZERO. The “endgame” recession may not happen immediately, but the post-COVID business cycle would certainly be shorter than policymakers had hoped. Paolo Maldini got his positioning wrong and his opponent has slipped past him.

It is not looking good.

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact