Edgar Fiedler, who served as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury in the Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford administrations, famously joked: “Ask five economists a question and you'll get five different answers – six, if one of them went to Harvard”. (Too often, all six of them will be wrong!) But looking at the latest global macro data, there should be plenty for economists to disagree about. In fact, the more I study this COVID-distorted economy, the more uncertain I feel about what is really going on. It is hard enough to understand what is happening today, let alone make forecasts (or, worse, try to identify new “secular” long-term trends). Yet consensus forecasts are all clustered around a unitary, Goldilocks-type macro narrative. This seems odd. With the possible exception of the period immediately after WW2, the economy we have today is not like anything we have seen before. So, rather than take comfort from the cosy sellside consensus, investors should try to test the sensitivities of these forecasts. New information over the next six months, if it provides some clarity, could profoundly shift current market narratives.

Much of the confusion about the current state of the economy has its origin in people trying to apply classic business-cycle analysis to COVID-19 macro distortions. For example, many investors want to know “where we are in the cycle”. But this is not a business cycle. Unlike most recessions, the economy did not contract in 2020 owing to some underlying macro imbalance or vulnerability. Policymakers shut the world down to halt the spread of a deadly pandemic. And they used a massive amount of stimulus to prevent the normal business cycle from taking hold (putting their economies into a sort of hibernation). Since then, it has largely been the course of the virus, not the usual battle between recession and recovery, which has been driving the trends we have seen. Describing “where we are” in this process as “early-”, “mid-” or “late-cycle” does not seem particularly useful. It is not even clear whether this is truly a “new cycle” or a continuation of the old one, regardless of what the economists at the NBER and OECD think.

Much of the confusion about the current state of the economy has its origin in people trying to apply classic business-cycle analysis to COVID-19 macro distortions. For example, many investors want to know “where we are in the cycle”. But this is not a business cycle. Unlike most recessions, the economy did not contract in 2020 owing to some underlying macro imbalance or vulnerability. Policymakers shut the world down to halt the spread of a deadly pandemic. And they used a massive amount of stimulus to prevent the normal business cycle from taking hold (putting their economies into a sort of hibernation). Since then, it has largely been the course of the virus, not the usual battle between recession and recovery, which has been driving the trends we have seen. Describing “where we are” in this process as “early-”, “mid-” or “late-cycle” does not seem particularly useful. It is not even clear whether this is truly a “new cycle” or a continuation of the old one, regardless of what the economists at the NBER and OECD think.

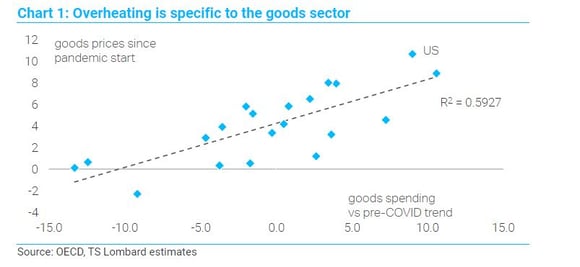

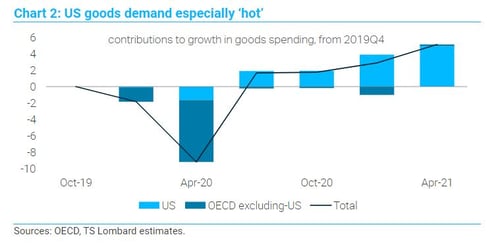

Faulty business-cycle analysis has unduly influenced the inflation debate, with rapid price gains assumed to be a sign of “overheating”. Yet GDP in most parts of the world is roughly where it was expected to be in the absence of the pandemic. And two years ago, the main debate was about whether the world was stuck in a liquidity trap, not how quickly inflation would decline from the highest levels in a generation. It does not make sense to think about this situation in terms of conventional “aggregate demand” and “supply” unless you take an extremely pessimistic view on post-COVID supply potential. Instead, most of the current inflation is a direct consequence of the pandemic. It came from consumers switching their spending from services to goods, plus the various distortions, logistical problems and bottlenecks in supply chains (an exaggerated bullwhip effect). Unlike in the textbook business cycle, what happens next to inflation is unclear because it depends on current distortions being resolved (if they are resolved). Will consumer spending patterns return to pre-COVID norms? Will supply chains adjust? We should not forget consumption is a “flow”. Having accumulated a vast stock of extra goods over the past 18 months, it is possible this flow will become significantly weaker as people shift back into services. And if goods demand falls (rare outside recessions) while supply chains recover, any notion of an “overheating” economy could totally evaporate in 2022.

Historically, economists have used the labour market to help them understand the cyclical position of the economy. The distance from “full employment” should determine underlying inflation dynamics. But labour-market data are a mess, too, right now, even as governments have unwound their various support measures. Given the rapid “recovery” in employment over the past 18 months, widespread reports of worker shortages, record levels of unfilled vacancies and – in some parts of the world – accelerating wages, it is easy to understand why some investors (and, increasingly, central bankers) think the labour market is also starting to overheat. Yet, again owing to COVID-19 distortions, it is hard to know how persistent these pressures will be. Worker shortages are concentrated in specific sectors. Record quits could reflect pent-up demand for job turnover after a period in which workers were too nervous to seek new opportunities. And recent wage gains – skewed towards the youngest workers – are not necessarily a sign of a permanent shift in bargaining power. Wages could slow once the reopening process is complete and some companies may even have the opportunity to cut wages if current worker shortages disappear.

In short, investors must be careful not to infer “new secular growth trends” from what might merely be “levels” effects associated with (and largely confined to) the pandemic. Perhaps the combination of supply disruption and policy stimulus has raised the level of consumer prices in the economy, without necessarily changing its longer-term trajectory. Certainly, the level of public debt has increased, as has the level of the money supply. And maybe we are now also seeing a shift in wage levels because the level of labour supply has shifted lower, especially in certain sectors. But this still looks quite different to what happened in the 1970s, where the money supply, wages and prices all spiralled higher (again, the better historical analogy can be found in the period immediately after WW2). Put another way, even if you believe the “excess-stimulus” hypothesis, there is no reason to think a one-off pandemic response will set in train a perpetual motion of permanently higher GDP growth and persistent inflation. The modern global economy – which has run aground on weak demographics and excessive private debt – better resembles that Evergreen tanker than got stuck in the Suez Canal in 2021. Macro policy is the tiny excavator.

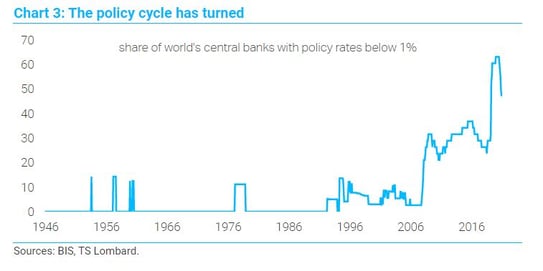

Despite all these uncertainties, one thing is abundantly clear: central bankers are no longer willing to wait for COVID-19 distortions to disappear. Spooked by the recent trajectory of their economies and aware of the mistakes their predecessors made in the 1970s, the authorities are now pivoting hard towards tighter monetary policy. This could be bad news for financial markets. While it is unclear whether central banks really need to squeeze aggregate demand, any attempt to do so must naturally start by inflicting pain on investors. As Paul McCulley reminds us, monetary policy always works via “trickle-down” economics.

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact