For months, investors have been “looking through” macro data and focusing on the prospects for a global recovery, with aggressive policy support – both monetary and fiscal – bolstering their confidence. With the global economy effectively “shut down” through April and May, many felt they could just ignore the macro news flow. After all, once it became clear global GDP would experience its biggest decline in 300 years, short-term data could no longer sway the market narrative. “Yes… but the economy was closed” became the common retort. Yet, four months after the lockdowns began, the data can tell us a lot about the economic consequences of the pandemic. This has implications for the strength of the recovery – and market sentiment – in H2.

So what have we learnt? First, all parts of the world – both DM and EM – are suffering deep recessions. We have been watching UK GDP closely, as it provides the most comprehensive measure that is available on a monthly basis. The latest data – published 14th July – show a 25% plunge in output between February and April, followed by 2% “rebound” in May. The UK lockdown started in the final week of March, though many people began ‘social distancing’ earlier. The government started to lift restrictions – slowly – in the second half of May. Obviously, the pandemic hit some sectors harder than others. The UK hospitality sector, which includes restaurants and hotels, suffered a complete stop, with output down 90%, while real estate (-3%), manufacturing (-25%) and financial services (-5%) fared better. While we don’t yet have comprehensive data for other nations, the OECD predicts similar declines everywhere.

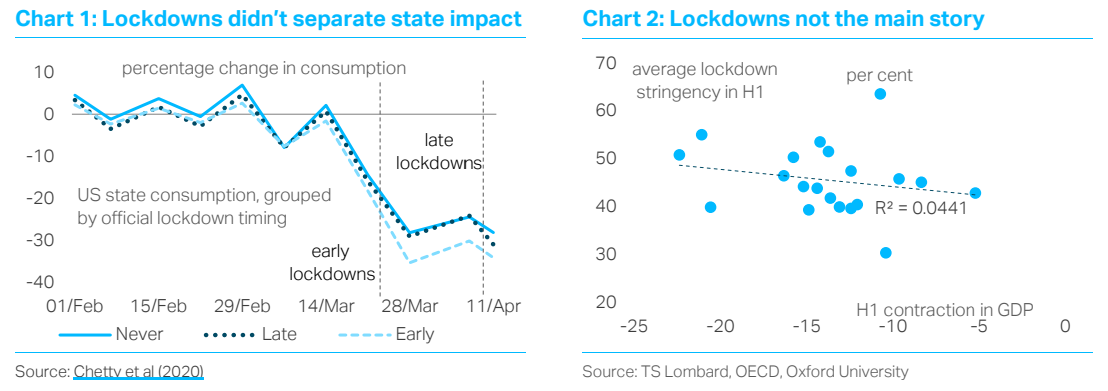

The second lesson is that official lockdowns explain only part of this weakness. It is fear of the virus, not the stringency of government laws, which prevent spending. In my recent blog Can Europe outperform during America's Covid-19 second wave?, I highlighted the performance of Sweden and Denmark, two neighbouring Scandinavian countries where governments enforced different lockdowns but consumers cut their spending by a similar degree. Several studies have now repeated these findings for the US, comparing state-level activity in jurisdictions with different levels of public enforcement. The chart above shows activity plunged before the US authorities introduced stay-at-home orders, with the severity of these restrictions not really influencing the depth of the decline. And on international data, we see only a weak correlation between OECD H1 forecasts and lockdown stringency.

The third lesson from H1 is that the pandemic has widened existing inequalities. Low-income workers were far likelier to lose their jobs, especially in sectors that require social interaction and were not compatible with digital working. Meanwhile, it was wealthy citizens who were more likely to cut their spending, imposing large negative spillovers on the rest of society. According to microdata from tracktherecovery.org, wealthier people have cut their consumption by around 15%, compared to just 3% for those who were actually more vulnerable to both the health crisis and the associated recession. And, of course, the stock-market rebound has amplified these inequalities, widening the gap between Wall Street and Main Street. This is a public relations disaster for central banks, who find they can influence markets more than the real economy.

If the main problem is fear of the virus – not govt restrictions – this has implications for the strength of the recovery. It means premature attempts to return to ‘normal’, unless they reflect genuine progress vs COVID-19, will fail. This theme is now playing out in many southern US states, which have struggled to reopen their economies amid a reacceleration in infections. But in other jurisdictions, including other US states and across much of Europe and Asia – where the authorities have made more progress in battling the virus – infection rates have continued to trend lower and this is allowing an economic recovery to take shape. What will this recovery look like? To answer this question it is helpful to look at China’s experience, which is further ahead in the reopening phase, having suffered its COVID-19 pandemic before the rest of the world.

Official Chinese data show a rebound in activity in April, just as the rest of the world suffered a dramatic collapse. Yet three months on, it is clear even China is struggling to get a V-shaped recovery, despite the government directly stimulating large parts of the economy (including real estate, public infrastructure and the investment of state-owned corporations). GDP has accelerated in May and June, but not all the way back to where it was before the pandemic. This is because some sectors of the economy, especially those that rely on social interaction, have continued to struggle. There is a marked divergence between manufacturing and services. While industrial activity has bounced vigorously, services and retail have experienced more muted improvements, with consumers remaining cautious even as the government eased the rules.

This manufacturing-services divergence is a theme that is set to play out elsewhere, for several reasons. First, we are likely to see more “pent-up” demand for manufacturing goods. Consumers that postponed purchases during the first half of the year will make up for these delays in the second half. China, which is famously the “factory” for the rest of the world, stands to benefit more than most, especially as its closure during January-March caused acute supply bottlenecks in other parts of the world. The Chinese authorities are also stimulating their economy, with a clear emphasis on boosting production – regardless of the level of demand. The second reason we should expect to see a more powerful recovery in global manufacturing than services is that many industries are less vulnerable to ‘social distancing’, especially for modern production processes that rely on machines rather than a large workforce. The OECD’s forecasts also assume a smaller decline in industry, followed by faster period of ‘normalization’.

So what’s the bottom line? After a pretty uniform plunge in activity, recoveries will become more uneven, both across national borders and by sector. Countries that have made more progress in containing the virus are better placed. But until the virus is gone, or a vaccine is found, there can be no return to normal. Global asset prices – especially equities – do not reflect this grim reality.

Read more blogs by Dario Perkins, Managing Director, Global Macro

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact