It is a cliché to say everyone’s experience of the COVID-19 recession has been different, but no sell-side economist ever shies away from using cliché to construct a narrative. For some people – especially those on the “frontline”, or those who experienced the virus first hand – it was undoubtedly a traumatic and devastating period of their lives. Millions more lost their jobs, facing economic hardships and uncertainty. Another group were put on official furloughs or temporary unemployment and could assume/hope the crisis would pass quickly – maybe they took up new hobbies or sat nervously watching the daily news on the TVs. Others found they could work effectively from home, though they somehow had to balance full-time employment with 24-hour childcare. Naturally, the economic impact has also been distributed unevenly, creating what commentators have dubbed the K-shaped recovery – ‘V’ for some people, “L” for others.

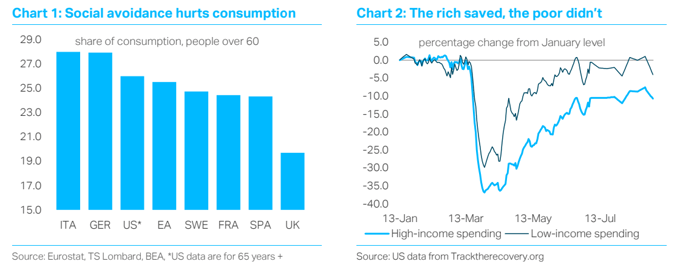

We see this ‘K’ across all sorts of “micro” divisions. Age is a good place to start. The dangers of COVID-19, of course, are heavily skewed towards older people. As we reopen our economies, without a vaccine, this is going to create huge divergences in consumer behaviour. Even as the young try to get back to something resembling “normal” – which has produced the “second wave” we are now seeing in Europe – older people will need to continue to social distance, shunning some forms of activity altogether. As the chart below shows, these people account for around 25% of aggregate consumption – their absence will hold back GDP growth. It will have a particularly large impact on specific sectors of the economy, such as accommodation and hospitality, which are struggling to recover from the pandemic (in contrast to e.g. retail sales).

The economic impact of COVID-19 has also been uneven across skill levels. Workers who are most likely to experience permanent job loss are those who work in low-skilled areas such as shops and customer-facing services. It is important to remember these sectors dominated employment gains during the last two decades thanks to the way labour markets responded to new technologies, especially computerization. People either “skilled up” and took complementary jobs in finance, tech etc., or they “deskilled” and found employment in areas that were not threatened by new technologies. Most OECD labour markets became polarized, with employment prospects collapsing across the middle of the skill distribution (areas such as manufacturing). COVID-19 could cause massive permanent job losses at the lower end, especially if social distancing accelerates the next wave of automation, the much-anticipated “rise of the machines’ – robotics, Virtual Reality, Artificial Intelligence etc.

Unhelpfully, we have also seen big shifts in consumer spending by income/wealth in 2020. The highest-income households, though they were less likely to lose their jobs in this crisis, have saved a higher proportion of their wages. Perhaps this is a feature of the lockdowns – which caused an “involuntary” rise in savings – but it also reflects fear and uncertainty. If anxiety fades, the rich might start to spend again. Continued recovery depends on it. But you have to worry about lower-wage citizens who didn’t adjust their spending in 2020 and have no savings or other financial resources to protect themselves from what might be a long spell out of work. And, of course, the powerful rebound in the stock market has further widened wealth inequalities after the pandemic – the top 1% own 50% of the stock market. People like to blame central banks, but remember the “detachment” of the equity market from the macro economy reflects the fact that large tech companies – which particularly dominate the US indices – face a very different earnings outlook to most SMEs (which the COVID-19 recession is hitting especially hard). Corporate divergences, a feature of the pre-COVID economy, have also widened dramatically.

Given these massive inequalities, it is not surprising we have ended up with a patchy and incomplete recovery in aggregate. The important question is what happens next. One possibility is that fiscal policy – not monetary policy – steps in to “even up” the outlook. As Michael Woodford pointed out at Jackson Hole, this can only happen with income transfers – not lower interest rates. Messing around with average-inflation targets is not a solution, however the Fed tries to dress up this policy. With supportive fiscal policy, perhaps the ‘tail’ of the K catches up with the head, completing the recovery. Yet there is a danger we go the other way, to the next letter in the alphabet – “L. This is where some sectors do not recover and as fiscal support fades, we get negative spillovers to the better performing parts of the economy. Consider, for example, the housing market, which has rebounded nicely in the US and the UK. How likely is it that activity in suburban areas continues to boom, even as demand – both commercial and residential – plunges in city centres, “permanent” unemployment rates hit previous recession highs and lending conditions deteriorate? And what would this mean for those areas of retail spending – such as home furnishing and DIY – that have been doing particularly well in recent months?

Now is not the time to take the K-shaped recovery for granted – it doesn’t look sustainable.

Read more blogs by Dario Perkins, Managing Director, Global Macro at TS Lombard

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact