Central banks have been raising interest rates aggressively for just over a year. During that period – the fastest and broadest monetary tightening episode in history – investors have been anxiously waiting for something to “break”, either in the world economy or, more likely, in global markets. Everybody knew the authorities have a habit of “breaking things”, especially when they focus on lagging indicators like jobs and inflation. In the minds of most, the only question was where these problems would appear first. Would it be in real estate, private equity, US tech or perhaps the hidden leverage in a variety of other COVID bubbles (including cryptocurrencies, NFTs and meme stocks)? Following the events of the last week, we now have an answer. And the thing that has broken is the one thing investors typically overlooked – global banking. Investors ignored this risk because, after what happened in 2008, stringent new regulations should have prevented another serious accident in that part of the system. So, what went wrong? And what does this mean for central banks as they try to battle inflation at multi-decade highs?

Hindsight is a wonderful thing, but it now seems alarmingly obvious that financial contagion would start at a bank in Silicon Valley. Closely tied to the tech boom of the last decade and especially leveraged to the idea or permazero interest rates, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) – and several of its peers – were acutely susceptible to US monetary tightening. Tech companies in the region had flooded the bank with large (uninsured) deposits, which the institution placed in long-dated US Treasurys as it sought to eke out yield differentials. Higher interest rates provided a double hit to their business model, killing the profitability of their customers and simultaneously undermining SVB’s capital position. Usually, of course, it doesn’t matter if banks make losses on their holdings of government bonds – particularly if they can hold them to maturity. But when SVB customers started withdrawing their funds en masse, egged on by social media and coordinated through WhatsApp, the bank was forced to realize those losses, creating an explosive feedback loop of bank runs and fires sales. This dynamic is as old as banking itself.

While SVB and its peers were uniquely exposed to COVID bubbles, this latest calamity has highlighted a broader problem in global banking – duration risk. Analysts everywhere are suddenly scrambling to calculate the interest-rate exposure of other institutions, with some eye-catching (but flawed) estimates already doing the rounds. In aggregate, of course, the banking sector has built up significant holdings of government bonds over the past decade, in large part because that is what the regulators wanted them to do. These securities were supposed to be safe, particularly in an environment where inflation was expected to remain low. But as some timely academic research has shown, the banking sectors’ exposure to “duration risk” is more complicated than just the value of the bonds it is holding. These institutions have also written fixed-rate mortgages, which means their profits gets squeezed when interest rates rise. Policymakers who took comfort from the idea that a rising share of fixed-rate mortgages would protect homeowners from rapidly rising borrowing costs (avoiding a GFC-style dynamic) forgot to consider who was on the hook for this shift in the structure of the mortgage market. It was always a zero-sum game. Stress tests are the best way to assess true duration risks, and this is an area where the US authorities have fallen behind Europe (particularly for the smaller banks).

With unrealized losses and costlier mortgage books, banks need to find ways to protect their margins – which usually means squeezing their depositors. So, they must try to keep deposit rates low, at least until their business models and balance sheets have adjusted to higher interest rates (note: higher interest rates are not a problem per se). In the current environment, this is proving difficult: not only have rates moved unusually quickly, but yield curves are deeply inverted (making maturity transformation costly) and depositors are starting to seek attractive returns elsewhere. Even if the largest banks, which tend to have stickier deposits, can protect their margins, this is not going to be easy for many smaller banks. The SVB failure has amplified this danger in the US by encouraging smaller depositors to move their funds into larger banks.

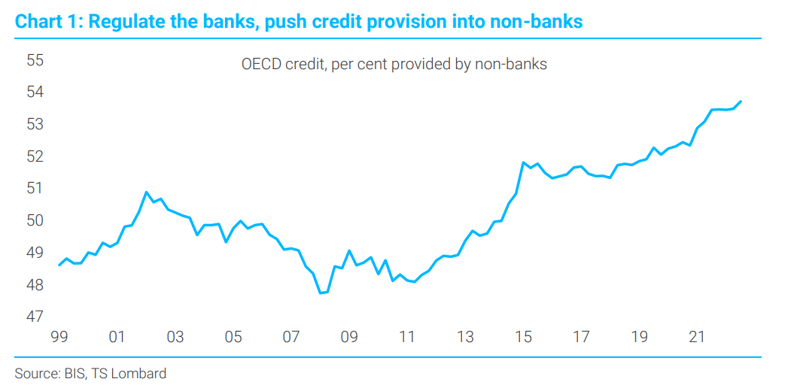

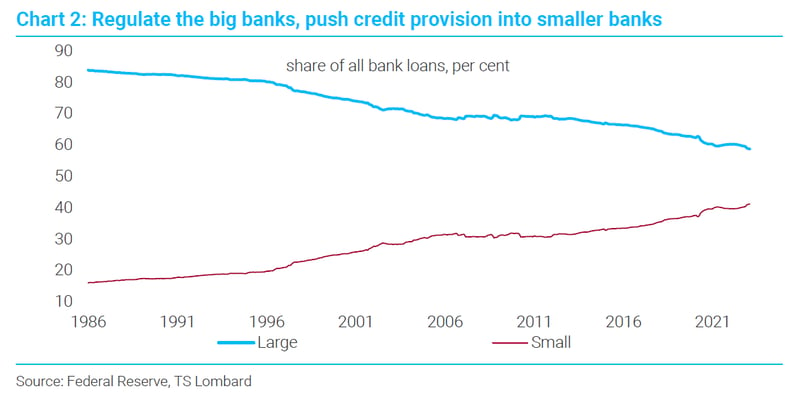

It is hard not to see certain ironies in what is happening in financial markets right now. US regulators focused on making the big banks safer but forgot that the smaller banks – which have been responsible for much of the credit creation of the past decade – could pose systemic risks, at least in aggregate. And global regulation encouraged banks to hold government bonds, while the other branches of government policy – monetary and fiscal – tried their best to create a world where interest rates would ultimately have to rise. This is another of the great ironies in macro policymaking, and a reminder that financial risk is viral in the sense that it mutates. This will not be a repeat of 2008, precisely because government policy has deflected the dangers into new areas. Instead, this is the ”crisis” you should have expected, based on policy designed to prevent an exact repeat of the previous crisis. To control is to distort. If regulations were the vaccine to the virus of financial risk, we just have to hope they have made the infection less deadly. The real danger for banks is not the current liquidity squeeze they are experiencing – which is easy to fix – but their longer-term credit risks. Commercial property is the sector to watch most closely.

What does this mean for the economy and the pursuit of lower inflation? At the start of the year, central banks wanted to keep monetary policy “tighter for longer”, with the aim of bringing inflation down in a controlled and gradual manner. Right now, they seem to be losing control of that process. As tensions build, banks – particularly the smaller ones – will restrict credit in a way that could have a devasting impact on SMEs, with powerful knock-on effects to aggregate demand. This will help the authorities to defeat inflation, but in a way that is uncontrolled and intractable, risking unnecessary hardship. While there are various estimates for what this credit squeeze means for “effective” interest rates (typically in the 75-150bps range), the reality is that this exercise is largely guesswork and central banks no longer have a good idea about the true “tightness” of monetary policy. To regain control of the disinflationary process, they must restore calm to the banking sector – even if that means, somewhat counterintuitively, targeted asset purchases, bailouts and potentially rate cuts. The Bank of England’s intervention last autumn provides the template. The BoE patched up the UK financial sector and maintained its monetary squeeze, but it never reverted to its previous (extreme) levels of hawkishness. Gradualism ruled.

Central banks are in a difficult position, caught between the (largely imagined) ghosts of the 1970s and their own PTSD from what happened in 2008. My guess is that PTSD will ultimately win out. The only question is how long it takes and at what economic cost.

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact