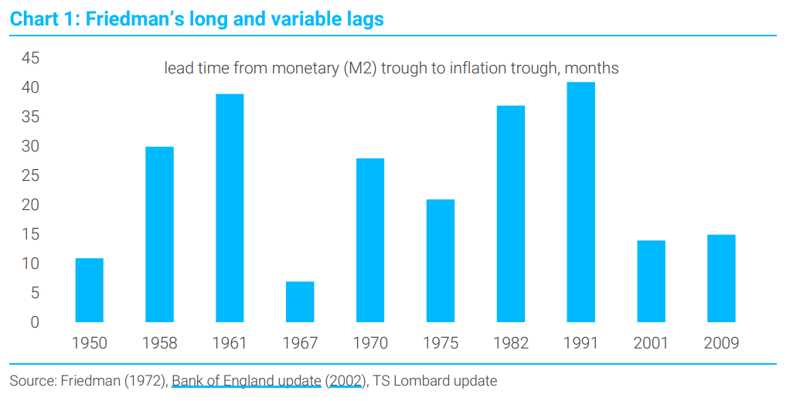

There is a bull market in sellside economists predicting recessions. Ask any of them why they believe 2023 will produce an even worse macro environment than 2022 and you can be sure the words “long and variable lags” will make their way into the conversation. And the logic seems sound. Even if central banks stop raising interest rates immediately, it is going to take some time for the full impact of their previous policy tightening to filter through the economy. We are about to see, not “pent-up demand”, but “pent-up demand destruction”. If you are old enough to remember the 2008 recession, you will recall that it happened in stages. First homebuilder sentiment collapsed. Then home sales plunged. Permits came next, followed by construction activity. But it was more than six months before we saw big job losses in the real-estate sector, and three years before the US economy suffered broad-based employment declines. The full impact of the Fed tightening cycle that ended in 2006 was felt only in 2008 (Though there is a debate about whether this episode was, in fact, two recessionary periods wrapped in one).

Like “liquidity”, “long and variable lags” sounds smart, which is probably why the idea is so popular on Wall Street. And this is not the first time in recent years that economists have recycled the ideas of Milton Friedman. But I would urge investors to think more deeply about what the phrase means. A cynic (not me, obviously…) would point out that this euphemism is just the monetary equivalent of saying “God works in mysterious ways”. We are certain that adjusting monetary policy is an effective and powerful way to manage our economies, it just happens that we cannot measure its impact precisely in real time. If you study the empirical literature on monetary policy – as I did for a recent Macro Picture on the monetary lags – it quickly becomes apparent that “long and variable lags” is just a convenient excuse to explain away decades of failure. It is a diagnosis by exclusion. Researchers have failed to identify a robust and stable relationship between monetary policy and the economy, so their conclusion is not that the link isn’t there (blasphemy!) but that it is state-contingent and liable to change. Central bankers, who have to hit an inflation target by tinkering with borrowing costs, are particularly keen on this explanation.

Before I get kicked out of the magic circle of market economists, I do have some good news for enthusiasts of monetary policy. Several recent academic papers suggest the failure to identify a robust relationship between interest rates and the economy is the result of poor research methods rather than a true indication that monetary policy does not work. The trick is to identify genuine monetary shocks and trace their effects through the real economy. This sounds obvious, but it is important to remember that there are causal links between interest rates and inflation running in both directions. High inflation makes central banks more hawkish, but tighter monetary policy reduces inflation. If you do not take account of these two-way linkages, you will get an empirical mess. 2022 was a good example of the sort of monetary surprise we are looking for. In a matter of months, central banks went from arguing inflation was “transitory” and required no response, to panicking about a potential rerun of the 1970s. With new research methods – including high-frequency market data and a better account of central bankers’ own internal analysis – we can identify previous episodes that were broadly similar to 2022. And when we do this, many of the old empirical puzzles disappear, leaving a more stable monetary impulse.

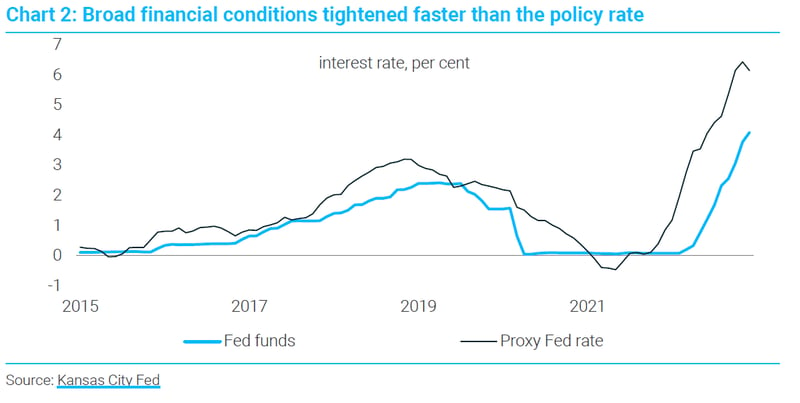

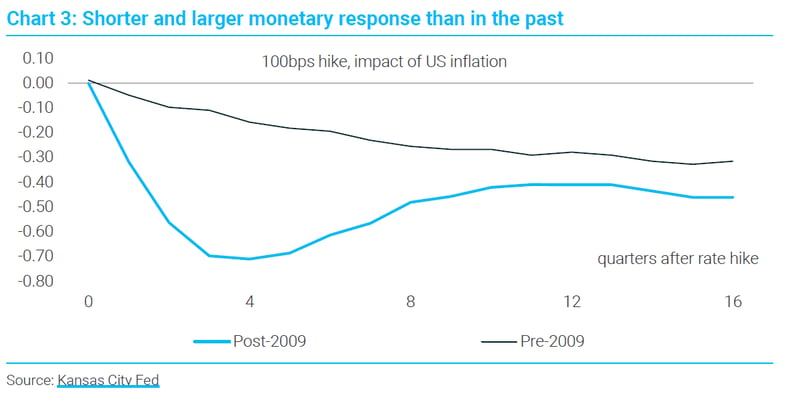

Why do these new research findings matter? The main implication is that it now appears the lags from monetary policy are shorter and less variable than we previously thought. That popular Friedman quote was based on faulty analysis. But there is more: evidence suggests not only that the lags are shorter than we previously thought but they have also become shorter over time. There are three potential explanations for this. First, central banks have become more transparent. By signalling their intentions far into the future, the authorities are able to guide sharper and more distinct turning points in financial conditions. Again, 2022 was a prime example. Markets promptly assumed a whole succession of rate increases, rather than adjusting slowly to every 25, 50 or 75bps hike. The effective interest rate charged on household and corporate loans increased rapidly. The second reason for shorter monetary lags is that central banks now use their balance sheets to further enhance their policy guidance. When they are doing QE, investors can be sure that policy rates will stay low for years, whereas QT should signal continued tightening. Third, in recent decades there has been a migration of the global credit system from banks to capital markets. Capital markets are more responsive to central bank signals, which, again, should speed up the transmission of monetary policy to the real economy.

Naturally, there are bound to be differences in the length of the monetary lags across different parts of the world. As is often the case in macro, much of the recent empirical work has been heavily US-centric. Financial structures vary and – as we have examined in previous research – there are particularly important differences in how mortgage markets react to higher interest rates. But, on balance, shorter monetary lags should be bullish for the global economy in 2023. Perhaps there is not as much pent-up demand destruction as everyone is assuming, especially for economies – like the US – that have a penchant for fixed-rate mortgages. Shorter lags would also mean that even if the global economy were to deteriorate more quickly than everyone is expecting, a prompt reversal in monetary policy could limit the damage. The supertanker is not as slow to turn as the consensus assumes. But the real question for monetary policy, of course, is about the response times of the central bankers who are guiding the ship. When the facts about inflation change, will they change their minds? Or have they still got something to prove, perhaps?

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact