Summary

Since the start of the year, global investors have been particularly keen to understand global monetary policy – in terms of both the impact interest rates are having on the macro economy, and the prospects for an imminent reversal in monetary policy. And it is fair to say there is a great deal of confusion out there, with some stark differences in opinion about whether interest rates are working and whether policy is “tight” enough to tame inflation(or trigger a recession). So, after a busy period of central-bank meetings all over the world (and seemingly endless commentary from officials, especially those who obviously enjoy the media spotlight), now is a good time to address the most popular questions. If you want to read more, check out my Macro Picture on this topic(request a trial below to do so).

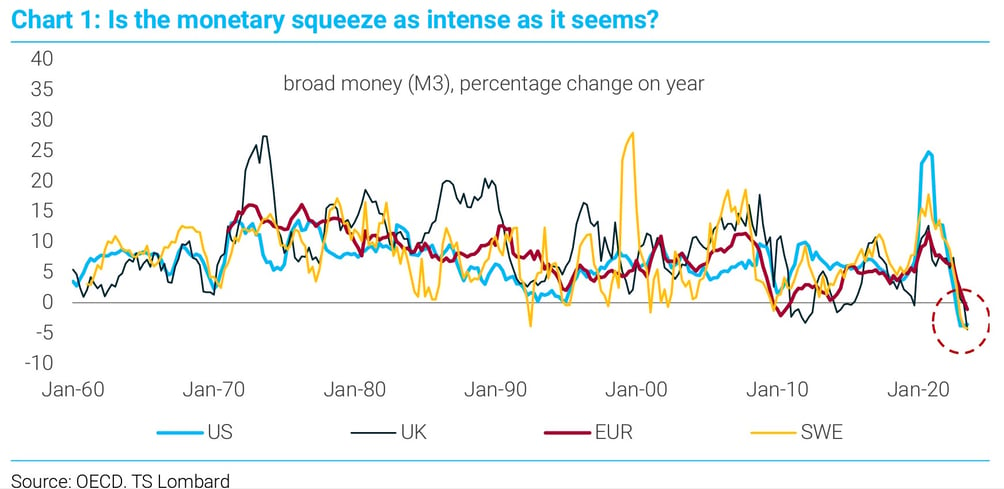

Q1: How tight is monetary policy anyway?

Unfortunately, there is no simple metric to answer this question. You could get a “precise” estimate from a Taylor rule, but that answer is sure to be precisely wrong, because two-thirds of the inputs in a Taylor rule – namely r* and the output gap – are largely fantasy. (So, GLWT.) If you’re a central banker, you want to see at least positive real interest rates, which has generally been the situation since the authorities ended their hiking cycle. Remember, the big complaint about monetary policy in the 1970s was that central banks failed to keep nominal rates above inflation, which is why they lost control of wage and price dynamics. (In reality, the whole thesis is full of holes – not that we need to get into that here.) While positive real interest rates are a (sort of) minimum requirement, central banks have a strange penchant for comparing interest rates with (largely fictious) measures of neutral, r*. Since r* is supposed to have declined over time, a real interest rate of, say, 2% is “tighter” today than it was 30 years ago. On the models that were popular before COVID-19, interest rates are generally in restrictive territory by as much as 200-300pbs, which is why central banks now have a clear easing bias. Ultimately, however, the appropriateness of the policy stance can be based only on how the economy is performing.

Q2: Is monetary policy even working?

Higher rates are supposed to work through two main channels: (i) intertemporal substitution (incentivizing saving and making it costlier to borrow) and (ii) income effects (squeezing the purchasing power of existing debtors). When we look across the developed world, we see that the first channel is working normally. Credit has stopped growing, and the most interest-rate sensitive sectors have suffered sizeable reductions in activity. Homebuilding has plunged and real house prices are down – and, in many cases, significantly so. But the second channel of monetary transmission has been much less potent than in the past. The reason is that many homeowners and corporates have termed out their existing loans, which has reduced their short-term exposure to higher borrowing costs. We should not forget that there has also been a lot of deleveraging since the global financial crisis, which has made debt levels more manageable at higher interest rates. The best way to assess the monetary squeeze from income effects is to look at debt-servicing ratios, which have increased only modestly compared with previous tightening cycles (especially the early 2000s). And with debt-servicing ratios staying low, there has also been a much smaller risk of financial distress (the dreaded “credit event”). If you want to understand why nothing has “broken” in this cycle, debt-servicing ratios are the key. (The only wobble has been among banks, which are the losers when other sectors have termed out their loans.)

So, the short answer to the above question is: Yes, monetary policy is working, but less than the more excitable pundits had assumed. And there have been offsets – such as fiscal policy.

Q3: Are broad financial conditions dampening the impact of higher rates?

This has been a question asked regularly throughout the tightening cycle, and it is true that broad financial conditions – as captured by the FCI metrics, which are popular in market punditry – have dampened some of the effects of higher rates, particularly when it comes to the wealth channel. If stock markets had stayed down or credit spreads had blown out, economies would be notably weaker today. But I generally push back against the importance of FCI metrics – for two reasons. First, these indicators do not capture the main parts of the transmission channel, particularly the credit channel – which depends on the level of interest rates and the availability of loans. If high interest rates are destroying construction activity and causing house prices to decline, this is a bigger deal for the economy than continued gains in the stock market (not least because wealth effects from housing are stronger than from equities). Second, central banks never have complete control over financial conditions. While optimism about the soft landing has kept markets in a bullish mood, a sudden deterioration in the outlook would transform the situation, leaving the authorities with a very different problem – trying to reverse a severe tightening in financial conditions. The BIS has shown that FCI metrics deteriorate later in the cycle, when recession becomes inevitable. But, in any case, central banks will not keep hiking just because stock markets are rising and credit spreads are narrow. They do not target asset prices!

Q4: Are higher interest rates a form of stimulus in disguise?

No. The economists who claim this (usually of an MMT persuasion) focus only on the income effects of monetary tightening. They point out that higher interest rates boost the incomes of savers and bondholders, while downplaying the hit to borrowers. And they totally forget intertemporal substitution. Of course, in principle, it is possible that the pure income effects could be net positive – particularly in the short term, if debtors have termed out their loans and deposit rates move quickly, or governments face large/immediate rollover needs. But even here, the sceptics of monetary tightening miss an important point: the marginal propensity to consume of borrowers is around three to five times higher than that of savers (that is why they are debtors!). So, if you take money away from private debtors and give it to bondholders, you are still generating a net monetary squeeze (this is called the “redistribution channel” of monetary policy). In short, the whole idea that higher rates are stimulative is wrong because it is based on a partial assessment of how monetary policy works. At the same time, it misses the point that a large chunk of public-debt servicing now happens via the central bank, in the form of interest on bank reserves. These funds won’t be recycled into the economy because that is not how banks make lending decisions.

To be fair to MMT, there was a time when empirical work on monetary policy often recorded positive effects from higher rates on inflation. This was known as the “price puzzle”, because it ran counter to mainstream macro. We now know, however, that this finding was largely the result of faulty empirical work. The price puzzle was common in studies that had failed to identify monetary shocks properly. Because central banks usually raise rates when inflation is increasing, it is not surprising that researchers can get the direction of causation backwards. In recent years, academics have taken great strides towards improving research on monetary transmission. Some of the most interesting studies in this area include: (i) using financial data to identify true monetary shocks (by, e.g. looking at the bond-equity correlation); (ii) concentrating on examples of exogenous monetary shocks (such as those that happened during the gold standard); and (iii) identifying changes in interest rates that were not a response to higher inflation (such as Sweden’s experiment with macro prudential interventions). In all cases, researchers found a robust, negative monetary impulse without the price puzzles that had been common previously.

Q5: If interest rates stay at current levels, will their impulse eventually fade?

Fed models show higher interest rates reduce economic growth for around two years but their impact then wears off. Presumably this is because the largest short-term hit is to residential investment, and once this has plunged – which initially reduces GDP – it will eventually find a bottom (so GDP growth recovers). In reality, the effects of monetary policy are more complicated. The big uncertainty is about how the income effects will play out, particularly the hit to borrowers, which will intensify as existing debts mature (the infamous “maturity wall”). For homeowners with 30-year mortgages, this isn’t a big deal. But a lot of mortgage debt is “fixed” at two- to five-year horizons, particularly in Europe, and a lot of SMEs loans (including in the US) are going to become costlier to finance over the next 18 months. Once debt-servicing ratios hit certain (unknown) thresholds, the incidence of financial distress will increase, which can only compound the damage from a given level of interest rates. The whole impulse from monetary policy suddenly become highly reflexive and non-linear. The point of cutting interest rates soon is that central banks can halt these dynamics before they kick in, and that will help secure the soft landing.

Q6: How will investors know if monetary policy is too tight?

Watch the monetary canaries, that is, the economies that always seemed particularly vulnerable to higher interest rates. If something breaks, it will surely break in those countries first. Right from the start of tightening cycle, we urged investors to keep an eye on Canada, Sweden, Australia, New Zealand, Norway, (to a lesser extent) the UK, and even certain parts of the euro area. These were countries where the income effects from monetary tightening were likely to be most potent, mainly because their private sectors were more heavily indebted (often because they didn’t suffer domestic banking crises after the GFC), and had a dangerous penchant for variable-rate borrowing or loans with short maturities. While it is encouraging that none of these canaries have croaked, some of them are beginning to look rather unwell, with labour markets that are flirting with genuinely recessionary dynamics. Sure, these economies are rarely in the spotlight for global investors – unlike the US, they are not going to be systemic for global markets – but the US was never going to be the first developed economy to buckle during the post-COVID tightening cycle.

Q7: How will investors know if policy isn’t tight enough (or r* has increased)?

There has been a lot of chatter about a second wave of inflation. For the most part, this is superstition based on what happened in the 1970s. The authorities will take a lot of comfort from how labour markets have evolved, because they are now in a very different state from how they looked two years ago. The “fundamental imbalance” in the economy (the post-pandemic mismatch between labour demand and supply), which was the main justification for monetary tightening, has largely disappeared. Based on this logic, it follows that central banks should start to worry about a second wave only if the progress they have made in labour markets begins to unwind. Should labour markets retighten, either owing to a strong rebound in vacancies or a notable acceleration in employment, officials would probably conclude that their mystical r* has increased. This would mean policy is not as tight as they thought, which – in the extreme – could provide the justification for new rounds of rate increases. (FWIW, I don’t think labour markets are particularly inflationary. In fact, a tight jobs market is delivering important macro benefits, including faster productivity and rising participation rates. Policymakers should let them run hot.)

Q8: When rate cuts begin, which central bank will cut the most?

Based on fundamentals, there are a bunch of central banks that should be cutting interest rates much more aggressively than the Fed – including the ECB, the BoE, the Riksbank and the Bank of Canada. These are central banks that tried to match Fed tightening in 2022, even though their economies were in a weaker starting position and had a much greater sensitivity to borrowing costs. In hindsight (not even in hindsight, really) the “reverse currency war” was pretty silly. It is clear, however, that many of the central banks that were whipsawed into chasing the Fed on the way up are still reluctant to diverge from US policy. At the same time, many of them have a gloomier take on supply-side dynamics, which has made them excessively worried about the dangers of premature easing (perhaps because their disinflationary progress has lagged the US experience). So, for now, it looks as if the first leg of the DM easing cycle will be fairly synchronized across countries. But perhaps some divergences will appear in 2025, especially if the monetary canaries finally croak and their central banks must go beyond risk management.

Q9: How far will the BoJ hike rates?

The BoJ believes it has a shot at genuine, sustained reflation. Wage dynamics have improved, and companies feel they can raise prices without fear of public recrimination. Consistent with my own views, the central bank now sees a structural case for higher inflation coming from the rest of the world, as a result of deglobalization and persistent labour shortages. And BoJ officials have even argued that domestic demographic trends are no longer a source of deflation, because the babyboomers are suddenly dropping out of the labour force en masse. But there is still a lot that could go wrong, which is why the authorities are desperate to nurture their reflationary theme rather than repeat past mistakes. This means avoiding premature policy tightening (fiscal or monetary) and preventing a sharp appreciation in the yen. While it made sense to end NIRP and taper QE, interest rates can rise only very gradually from here. (BTW, we see a bullish case for Japanese equities even if the authorities are not completely successful at de-Japanization.)

Q10: How much has QT compounded (or past QE undermined) global monetary tightening?

It hasn’t. QT is pointless virtue-signalling. Central banks do it just to just to prove that their previous asset-purchase programmes were not a form of debt monetization. They also think it demonstrates their independence. Both ideas are silly. But in terms of the policy’s impact on monetary conditions and the broader economy, the effects have been negligible. Contrary to what many pundits believe, there is no robust link between official “liquidity” injections and asset-price performance (let alone GDP or inflation). That is because, in the modern collateralized debt system, true “liquidity” is endogenous to risk appetite; it is not a function of whether a central bank is increasing or shrinking its balance sheets. Perhaps the most favourable thing we can say about past QE is that it provided a credible form of forward guidance, because we knew a central bank that was engaged in a multi-year asset purchase programme would not raise interest rates anytime soon. But even that assurance has been diluted since the pandemic and we know that the same policy signal cannot apply in reverse (because the decision to engage in QT tells us nothing about where policy rates are headed). And while it is possible that destroying bank reserves might eventually cause problems for the “plumbing” of the monetary system, the authorities are now well aware of these risks (unlike in 2019) and will respond forcefully.

Bonus Q&A for X (where this question comes up A LOT): Are we in a world of fiscal dominance and is THAT the reason monetary policy “doesn’t work”?

Loosely, fiscal dominance is where government budgetary decisions undermine the ability of central banks to hit their inflation targets. In extreme situations, the CB may even abandon its target altogether. Usually, we think of fiscal dominance as a situation where deficits are too large. If the central bank raises interest rates to tame inflation, it will add to the pressures on the public finances, potentially leading to even larger deficits and worse inflation. But you could also argue we had a sort of fiscal dominance after the GFC, when government austerity compromised the ability of the monetary authorities to meet their objectives, especially when rates were at the ZLB.

Does fiscal dominance apply today? It is true that fiscal policy has added to inflationary pressures since COVID-19, while helping to keep growth resilient in the face of higher interest rates. But this does not mean we are going to see fiscal-induced inflation on an ongoing basis, or that central banks have tacitly given up on their targets to support the public finances. There are two reasons. First, it is hard to generate an ongoing inflationary impulse from fiscal policy alone. That would require ever increasing deficits, which is not what we are seeing currently (structural fiscal balances are generally improving). Second, central banks are keen to ease monetary policy, NOT because they are worried about the trajectory of the public finances (or because they are being leaned on by government officials), but because they are worried about triggering an unnecessary recession. They believe, from a medium-tern perspective, a modest inflation overshoot is more desirable than putting millions of people out of work. While this approach tends to anger the “sound money” people on X, it was perfectly predictable – I wrote about it two years ago when I said central banks would show a “revealed preference” for higher inflation if it turned out that the “last mile” back to 2% was particularly hard or slow. Of course, the authorities can only tolerate higher inflation as long as there are no signs of the spirals that occurred in the 1970s. If wages reaccelerated or inflation expectations started to rise, they would have to rethink the strategy.

To sum up, “fiscal dominance” sounds cool, but it is not what we have today. I prefer the term “fiscal prominence”. This is where governments will play a more active role in the economy than they did in the past (through larger deficits and strategic industrial policies) but this does not lead to a large/persistent inflation overshoot or an eventual budgetary crisis. Instead, we have just stumbled onto a more reflationary fiscal-monetary policy mix than we had during the 2010s. And to the extent a higher-pressure economy will boost productivity, this could even be a good thing.

For more from Dario please request a trial to our research, (certified investment professionals only, please)

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact