Andrea Cicione, our Head of Strategy, and Steven Blitz, our Chief US Economist, answer the following 7 questions:

- Equity markets have rallied on the back of unprecedented fiscal and monetary support. Why do we think they will roll over again?

- Infection rates have peaked and lockdowns are being eased. Isn’t the worst already behind us?

- If medicine is the key and all the pharma giants are researching cures and treatments, should we not be bettting on seeing success soon?

- If earnings will recover next year, why not look through the shock and price for future performance?

- Why can’t the Fed (and other central banks) just keep supporting asset prices until the real economy recovers?

- Will central banks follow the BoJ and start buying equities?

- When do we think the “reality gap” between market pricing and our view will close?

1. Equity markets have rallied on the back of unprecedented fiscal and monetary support. Why do you think they will roll over again?

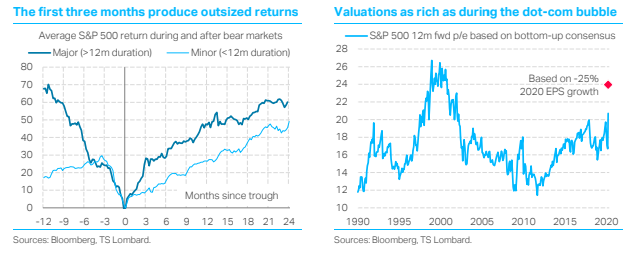

Over the years, equity investors have been conditioned, almost in a Pavlovian fashion, to chase up the market, especially when central banks “have their back”. The Fed is committed to expanding its balance sheet indefinitely. This is entirely unprecedented. As liquidity ultimately finds its way into the stock market, it is not surprising that equities have rebounded sharply at roughly the same time as the Fed asset purchases began. Investors know that the strongest equity returns in a market recovering from a bear are achieved in the first three months of the rally. Blink and you’ll miss them. As expectations are the most important factor for equities, it is the expectation of abnormally high returns that can, in fact, lead to precisely that outcome.

But if anticipations of a swift recovery in macro and corporate data are misplaced – as our analysis says they are – the equity market can quickly deflate. Besides, based on bottom-up expectations of just 7% EPS contraction this year, the S&P 500 is trading at a higher p/e than before the Covid-19 crisis. Using more realistic EPS growth estimates of -25% (our forecast, see below), the US benchmark is trading at about 24x forward earnings. Such expensive valuations have not been seen since the dot-com bubble was in full swing.

Medical treatment, ahead of the discovery of a vaccine, will likely determine the trajectory of the economy more than any monetary or fiscal policy. It is therefore true that the biggest “threat” to any bear position is the appearance of medical treatment that, at the very least, makes a virus infection far less dangerous. Much is made of quinine-based treatments and Remdesivir, but these are only for patients already ill enough to be in hospital.

To combat Covid-19, there are currently 10 therapeutic agents in active trials and another 15 in the planning stage. Some of the most optimistic researchers reckon a vaccine could be produced by September, but trials have not yet started. A new vaccine could take 12-18 months to be available to the public. Also, there are always false leads. Some practices in place include already-approved drugs, thereby skipping ahead in the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) timeline to clinical trials, while the FDA itself has responded to quicken the time to a solution with its Coronavirus Treatment Acceleration Program (CTAP). But this is still only a shortened timeline, not the elimination of a timeline altogether, and there is no guarantee that a treatment can be found quickly. In the end, the quickest route to reduced infection and a reopened economy is the broad adoption of behaviour that reduces the risk to health.

Whatever happens, individuals will continue to be cautious and economic activity – and therefore earnings – will remain suppressed. The timescale described above suggests consumer caution will be prolonged far beyond what the stock market is currently discounting.

4. So, if this is a one-off shock to earnings (and growth), and they’ll both recover next year, why not look through the shock and price for future performance?

We expect S&P 500 2020 EPS to contract between 20% and 30%. With a conservative 16x forward p/e ratio to this level, our S&P target is below 2000. But what if investors ignore this one-off shock and focus on 2021? Would 2020 even matter?

We think it would. First, the amount of earnings decline projected for this year determines the starting point for expected earnings in 2021. Second, we forecast that earnings growth in 2021 will be in single digits, as we see a gradual economic recovery. Given the medical aspect described above, the outcome could as well be worse than this – the risks are symmetrical. But even taking the bottom-up consensus of 2021 EPS growth of 18% at face value, we are looking at earnings at the end of next year of about 142 (160 or 2019, 120 or -25% for 2020, 142 or +18% in 2021). 2y-forward multiples are typically 1.7 lower than 1y-forward: a 14.3 forward p/e

ratio still gives an S&P level in the region of 2000.

The Fed, like any central bank, can theoretically grow its balance sheet without limit and while this can affect market prices through improved liquidity, it cannot guarantee prices will be at a certain level. Before Covid-19, Fed liquidity helped push up equity market multiples against the backdrop of rising growth and earnings, but a sharp downgrade of underlying fundamentals changed investors’ views of value and the equity market followed suit.

The Fed has recently started to buy investment grade corporate debt and limited high yield paper (by law it is prohibited from taking losses, but having Treasury invest in SPV and provide credit protection is insurance against some risk). This raises the question of liquidity vs solvency. There is an obvious interconnection: liquidity allows solvent firms to have access to markets, notably those that have lost 90% to 95% of revenue but expect revenue to return once the economy reopens. The Fed very much wants this financing to be possible. The solvency question moves beyond the Fed’s capacity when considering how long the shutdown lasts, the nature of the restart and the risk of recurrence – firms with permanently lost or sharply diminished business will shut down and default, and Fed actions are not intended to – nor indeed can they - alter that reality. The illiquidity part of credit spreads narrowed on the Fed’s actions, but as market participants begin to recognize more the full extent of this downturn, credit spreads will widen once again – this time to reflect greater default risk. Longer term, the problem with the Fed or any central bank being owners of huge amounts of assets is that it obliterates risk pricing in the market and the misallocation of capital that ensues will, over time, lead to more problems than are solved by asset purchases in the short term – the botched QT effort of 2018 serves as a reminder of how this problem manifests itself.

7. When do you think the “reality gap” between market pricing and your view will close?

Since 1929 there have been eight “major” bear markets (i.e. that lasted more than 12 months) and four “minor” ones (shorter than 12 months) in the US. The average drawdown has been 48% for the former and 26% for the latter. All the major bear markets experienced, on average, 2.5 unsustained rallies that only led to the S&P 500 making new lows. These average rallies were 18.5%, with a range of 10%-46%. Of the minor bear markets, however, only the 1987 one witnessed mid-cycle rallies – two of them yielding temporary gains of about 15% and 12%. The current bear is large but should be short-lived. It will likely last less than a year, since it started very suddenly; but it will take closer to two years for the market to make a full recovery.

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact