Both the Fed and the ECB have grabbed headlines recently with talk of central bank digital currencies (CBDC). But of all CBDC projects currently in the works, it is the one by the People’s Bank of China that is nearest completion. The bank has been working on a digital currency electronic payments system (DC/EP) since at least 2014. Trials are in advanced stages and a limited roll-out is likely in 2022/23. The key goal is greater oversight of the payments system. With regard to monetary stimulus, we think the most likely application of DC/EP is targeted cash and credit provision.

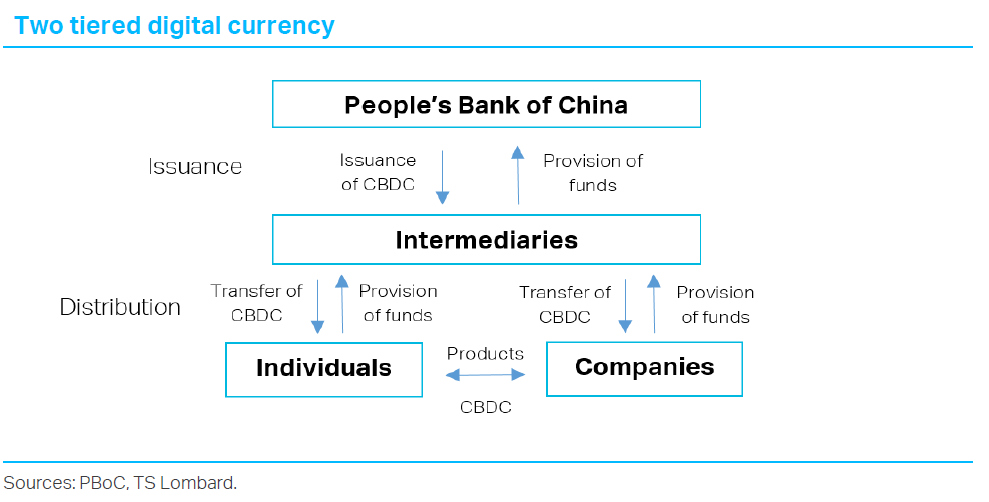

China’s DC/EP will operate on a two-tiered system (see the chart below). The digital currency itself, like cash, is a direct claim on the central bank denominated in RMB. The PBoC will exchange CBDC with chosen banks and financial intermediaries, which, in turn, will make the funds available to retail users via existing electronic banking platforms. Clients will be able to convert RMB to CBDC (at a rate of 1:1) via their digital wallets.

The PBoC will keep a ledger of all transactions and provide the core payment infrastructure, while intermediaries such as banks, telecoms and other payment providers offer services to the public. The two-tiered system aims to prevent disintermediation of existing financial institutions and to lower the concentration of risks at the PBoC. To further limit disintermediation, the PBoC has stressed that the DC/EP will be non-interest bearing.

The underlying infrastructure that records all transactions is “permissioned” distributed ledger technology (DLT) backed up by a conventional database. DLT works on the same principle as bitcoin and the underlying blockchain, whereby transaction information is stored across a network. However, in contrast with bitcoin, the PBoC has chosen to operate a “permissioned” DLT network, this means that, in effect, the Bank is the final arbiter of transaction authenticity and of what data are stored on the DC/EP system. This confers an incredibly powerful role on the bank, enabling it, in theory, to rewrite the history of DC/EP transactions.

The architecture of DC/EP is similar to those trialled by the Riksbank and the Bank of Canada – the next most-advanced CBDCs. The PBoC’s version differs in one crucial way: no anonymity of users. The Riksbank and the BoC will record transactions on permissioned DLT systems but will not link them to real-world identity. Another important distinction is that DC/EP user-to-user transfers can occur offline. This is a key feature for DC/EP take-up in rural China.

We expect limited national use sometime after the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics. A phased approach will be taken, initially limiting the amount of RMB that can be converted into digital currency. Once “live” partial adoption of DC/EP is likely to be rapid. There is near total prevalence of mobile payment in China, down to street sellers and villages, meaning consumers are already habituated to card-less e-payment. Furthermore, government regulation mandating that all vendors who currently accept Alipay and WeChat pay also accept DC/EP ensures a ready supply side. Moreover, the same prevalence and spending habits mean that data privacy is not a major issue against adoption. The Alipay-WeChat duopoly (94% of non-bank payments) is nominally private; however, users are aware their messaging and transaction data are available on government request. This is different from the immense power that DC/EP confers on the PBoC, but the magnitude of that difference is unlikely to be appreciated by the average user.

The goal of DC/EP is control and data collection. The aforementioned rise in mobile payments has already caused significant disintermediation of the traditional financial system. Mobile payments accounted for 70% of all electronic payments in Q2/20, up from just 40% in Q2/13. DC/EP will offer an alternative mobile payment system to the existing duopoly. It will also provide direct PBoC control of the payment infrastructure. We do not think DC/EP will accelerate the disintermediation of banks. Rather, by weakening Alipay and WeChat, the digital currency could halt or reverse the migration of users towards fin tech firms.

Omnipotent PBoC. The data collection aspect of DC/EP is understandably very appealing to the CCP. The permissioned DLT infrastructure would provide accurate, information on all digital RMB transactions. The wealth of data available on spending habits and wages paves the way for significantly increased surveillance of individual financial behaviour. Moreover, as the PBoC controls what goes into the ledger, it would have the ability to determine financial transaction “truth”, deciding which payments to validate and which to ignore. DC/EP also paves the way for negative interest rates on consumer deposits, although China is far from the zero lower bound.

The reality, is more mundane: targeted spending. The ability to credit individual accounts and enforce on what and where the digital currency is spent, means China could engage in precision credit and consumption stimulus. The applications are wide-ranging – from small-scale welfare/poverty relief transfers to province-level grants for infrastructure FAI. Government workers in Suzhou already receive their transport subsidy in DC/EP. While Shenzhen gave away RMB 10 mn in a DC/EP lottery today, to boost consumption and trial the digital RMB. Enforcing spending restrictions or simply tracking the funds from account to end-use limits waste and reduces the risk of credit spilling into speculative property or financial investment. Should trials prove effective the PBoC’s expanded toolkit could set a much lower threshold to undertake micro stimulus measures, and conversely a higher bar to engage in broader credit easing.

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact