A simple narrative is taking over financial markets, especially the short end of the yield curve, where the idea that central banks are “behind the curve” is rapidly gaining traction. Initially, it was just the emerging markets that were hiking; now there is growing pressure on the RBA (whose yield control is looking increasingly shaky), the BoE (largely self-inflicted), the Fed and even the ECB (as if Jean-Claude Trichet were still around). Unexpectedly high and broadening global inflation is clearly a big part of this story, with many commentators increasingly blaming “excessively strong demand”. Central banks, spooked by the threat to their credibility (whatever that means), will raise interest rates in an effort to squeeze this excess demand out of the system. But the true inflation story is more complicated than this narrative implies. Sure, there is a demand element to it, but the problem is relative demand for goods versus services. And there is also a critical supply-side element – persistent COVID disruption, which, rather than diminishing, is now showing strong reflexivity. While it makes sense for central banks to sound hawkish – a sensible “risk-management” strategy – the situation does not warrant an urgent response.

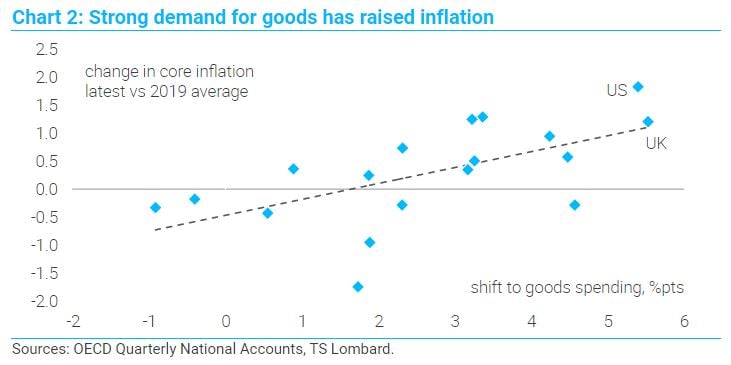

Let’s look at these issues in more detail, starting with the relative demand shock. Since the start of the pandemic, consumers have shifted their spending from services (“experiences”) to goods (“stuff”). The classic example was buying home gym equipment rather than renewing your gym membership. Or buying a new TV rather than going to a concert. Everybody focuses on the situation in the US, which provides the most comprehensive and timely data, but these trends happened everywhere. Yes, policy support was a critical part of the story because without the stimulus of the last 19 months, we would be looking at a totally different inflation narrative – deflation and the risk of a persistent slump. But the idea that this was just about Americans spending their stimulus cheques on Chinese goods is a massive oversimplification. The problem is that these shifts in spending have not reversed as quickly/fully as everyone expected. Worse, consumers are bringing forward Christmas spending because they fear yearend shortages.

Let’s look at these issues in more detail, starting with the relative demand shock. Since the start of the pandemic, consumers have shifted their spending from services (“experiences”) to goods (“stuff”). The classic example was buying home gym equipment rather than renewing your gym membership. Or buying a new TV rather than going to a concert. Everybody focuses on the situation in the US, which provides the most comprehensive and timely data, but these trends happened everywhere. Yes, policy support was a critical part of the story because without the stimulus of the last 19 months, we would be looking at a totally different inflation narrative – deflation and the risk of a persistent slump. But the idea that this was just about Americans spending their stimulus cheques on Chinese goods is a massive oversimplification. The problem is that these shifts in spending have not reversed as quickly/fully as everyone expected. Worse, consumers are bringing forward Christmas spending because they fear yearend shortages.

Over time, it is likely that spending habits will continue to shift back to pre-COVID norms. But until then, the current situation is compounding the pressures on global supply chains, which have not yet had the chance to recover from the dislocations they experienced at the start of the pandemic. Instead, a supply crunch that initially made it hard to secure specific items – luxury cars, toilet rolls, PlayStations – has morphed into a full-blown international crisis. In general, this supply-chain problem is threefold: (i) shortages of specific components (e.g., semi-conductors, magnesium for EV batteries, iPhone components and textiles); (ii) severe transport delays; and (iii) a shortage of workers in specific industries (e.g., truck drivers in the US, across Europe and even in Indonesia). Worse, we are seeing severe reflexivity, where the problems in one part of the supply chain cascade, amplifying the strains elsewhere. This is an example of the bullwhip effect, but it is happening on an unprecedented scale (as you might expect after the biggest decline and rebound in global GDP for 300 years). Supply chains have never been stressed like this before, and it is remarkable we have not had a total systemic collapse – yet!

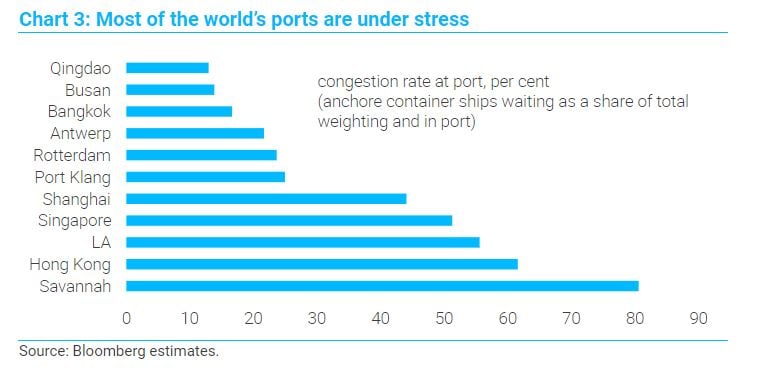

The “shortages” angle is now widely recognized but rolling lockdowns in Asia, energy rationing in China and periodic bouts of extreme weather (the odd typhoon here and there) are making it only worse. When the system is operating at full capacity, there is no margin to absorb such problems. When European car producers cannot secure enough semiconductors, they have to halt production altogether, causing output and sales to plunge. The strains in the transport system are also well covered in the media, even if much of this coverage is US-centric. Everyone is aware of ships queueing outside Long Beach, but it is important to remember that almost 80% of ports around the world are suffering similar issues. Waiting times have increased at Felixstowe, Rotterdam, Antwerp, Hong Kong, Singapore and Shenzhen.

There are lots of different angles to the problems in global transport, but the key point is that they interact and amplify one another. Dockyards cannot unload product quickly enough, which causes traffic jams outside the ports. Truck drivers cannot make as many trips per day, which slashes their hourly wage; as a result, they look for work elsewhere – compounding the labour shortage. And as containers stack up in the docks, there is no capacity to unload ships, which further lengthens waiting times. Internationally, there is also an imbalance in the demand and supply of containers, making the whole system work less efficiently. Ships that took medical supplies and PPE to Africa and South America left their empty containers behind, while perverse price incentives encourage US ports to send empty containers back to Asia rather than move them inland to be re-used for US exports. Meanwhile, there are fewer passenger flights, which means more cargo has to travel by ocean. And when retailers over-order to ensure they have sufficient stock for Christmas, they keep those extra products in their original containers, which compounds the shortage elsewhere, widening the imbalance. The strains feed on one another.

How long will these issues persist? The consensus is assuming the situation will improve by the spring – the Chinese New Year is a key date, once we get past the busy Christmas period for the US and Europe. But, ultimately, the answer depends on how quickly consumers rotate back to services and whether those parts of the world that have been deploying a zero-COVID policy will need to continue using rolling lockdowns in 2022. While the problems could persist for longer, it is equally plausible that the situation could reverse faster than the consensus is assuming. Combine continued consumer substitution with a serious economic slump in China and a post-Christmas lull in transport (which allows supply chains to catch up – possibly overcompensate, if the bullwhip effect moves into reverse) and we could even see a quick deterioration in world trade and global industrial production. Since financial markets are always oversensitive to traded goods prices, this might even spark a new deflation scare in 2022.

Tighter monetary policy is not a solution to these problems, since this is not a story of aggregate demand being too strong. Rather, central banks should wait to allow the relative demand shock to unwind and let supply chains adjust. But it is clear they are worried that high inflation is beginning to undermine their credibility. Naturally, those central banks that are most insecure will strike first. But panicking now and bringing forward rate hikes would be a sign of monetary weakness, not strength.

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact