This is the time of year when economists across the financial sector are busily marketing their chunky ‘year ahead’ volumes. There is an old joke that the savvy investor should take note of whatever consensus emerged from this exercise and put the opposite trade on just ahead of Martin Luther King Day (which this time falls on 20th January). Last year, the consensus was looking shaky even before January, when the December plunge in stock markets took everyone by surprise, threatening to trigger another globalized recession. And in January 2018 we had the infamous ‘Volmageddon’ episode, which didn’t match the prevailing ‘melt-up’ narrative.

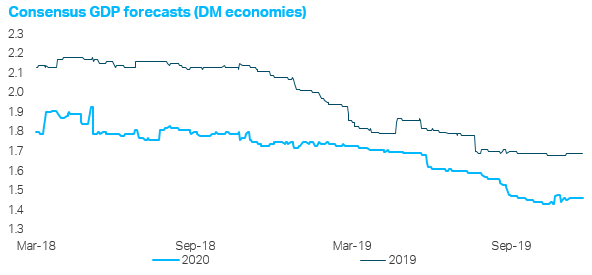

Looking at 2019 as a whole, it is certainly true the macro economy hasn’t evolved the way most economists were expecting. Growth everywhere dipped more sharply than the consensus expected and there was no sign of the inflation pressures that had dominated economists’ thoughts throughout 2018. Still, central banks provided the most notable surprise of the last 12 months. Far from obsessing over the Phillips curve and ‘normalizing’ interest rates, as the consensus had assumed, the authorities abandoned their old analysis and promptly eased policy, making every effort to extend the macroeconomic cycle. Risk assets duly rebounded.

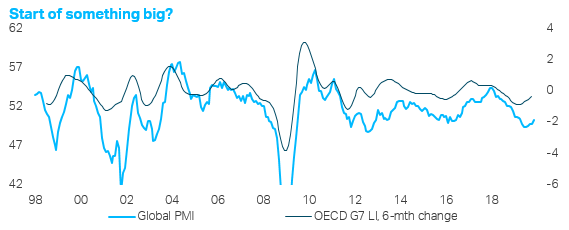

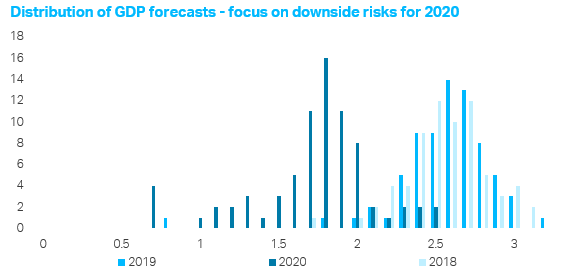

Pulling together a consensus for 2020, it is clear most of the industry is fixated on the downside risks to the global economy. While few economists are prepared to forecast outright recession – instead they have typically pushed any serious problems into 2021 (because the next recession is always 18 months away…) – they include a long list of things that might go wrong. Despite this nervousness, most economists are projecting a gradual recovery over the next 6-12 months. This reflects the recent stabilization in broad leading indicators, the continued resilience of the US labour market and even a few scattered signs of ‘green shoots’. Most investors have also been assuming a ceasefire in the trade war between the United States and China, which should deliver a modest revival in capital spending, boosting the global industrial cycle.

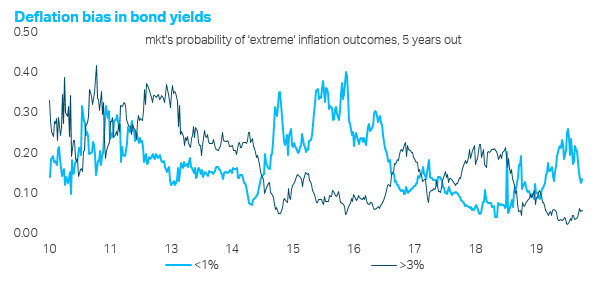

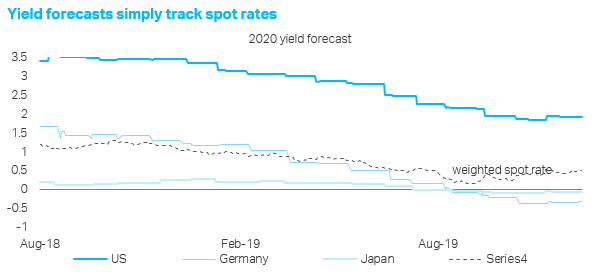

Compared with the last couple of years, there has also been a notable shift inflation expectations. Most economists have given up on the idea that consumer prices will eventually accelerate above central banks’ targets and are now predicting subdued inflation far into the future. Even the hawks have capitulated, which has created a clear disinflationary skew to long-term bond yields. Unsurprisingly, this has reinforced already dovish expectations for monetary policy. The consensus expects central banks to stay on hold in 2020, with a slight easing bias.

Where could the consensus be wrong? Capitulation as fast as what happened in 2018 or 2019 would probably involve a major geopolitical event (Iran?), another flare up in the ‘repo crisis’ or a sudden deterioration in dollar liquidity. Obviously investors must watch the US-Iran situation closely, but as far as those other risks are concerned, the Federal Reserve’s aggressive efforts to try to calm money markets has clearly helped to address any near-term market vulnerabilities. In fact, if there is no further escalation in the Iran situation, the trade deal is signed soon and Brexit-related risks continue to diminish, we might even see a sustained boost to investor sentiment in early 2020 (dare I say it, perhaps even a ‘melt up’). The question, of course, is whether improving market confidence will actually translate into materially stronger economic growth. Anything beyond a mild improvement in activity would take economists by surprise, especially as the consensus is struggling to identify any genuine ‘upside risks’. We are worried about corporate earnings, which are not only a risk to equity valuations but also provide the clearest ‘late-cycle’ macroeconomic vulnerability. As far as fixed income is concerned, the skew towards sustained disinflation risk leaves markets acutely vulnerable to even a modest acceleration in consumer prices. Central banks have said they would welcome an ‘overshoot’, which means the hurdle for policy tightening is now unusually high. But the question is whether the data will test this new monetary regime in 2020. While an inflation outbreak is not likely, this is definitely something to watch.

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact