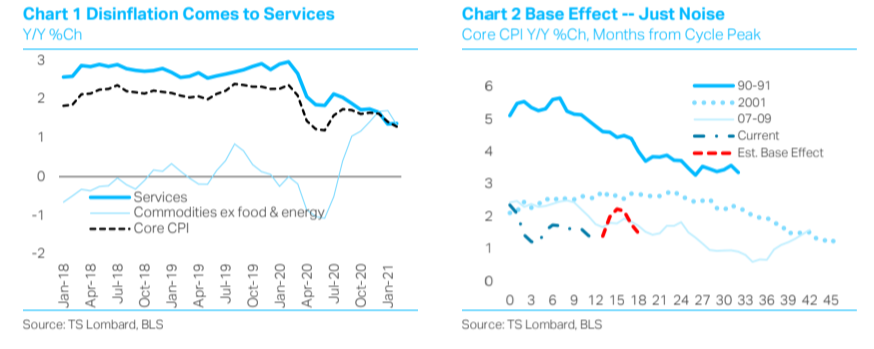

Any inflationary process must wait for short rates to drift above what the Fed pays for bank reserves, until then its price changes inside a post-recession disinflationary trend. February CPI data underscore the disinflationary trend underway, and our guess is that this trend has several more months to run. Most telling is service inflation dropping off on a year-over-year basis to around 1.4% (1.2% ex rent) after averaging 2.7% in the two years leading up to the Covid shut-down (see Chart 1). Looking at the CPI rent-metrics, owners’ equivalent rent of primary resident rose 0.3% m/m in February after a string of 0.1% increases, while rent of primary residences rose 0.2%. It looks like higher home prices are starting to come into the index (owners equivalent comes from asking people how much they could get from renting their house). The sharp deflation in urban centre rents has yet to make its mark in the price indices, along with urban condos (or so it seems). Good prices ex food and energy, less important to core CPI but not to most people, have begun to edge lower, dropping to 1.3% y/y from 1.7% y/yin the past two months. Volatility rules this series, but I suspect the tendency of its average to mean revert to zero takes hold later this year once inventory has caught up to sales.

Even more hyped than inflation risk is the base effect – the jump in y/y inflation from the low base in May 2020. If we assume core CPI grows monthly at the same average pace of the past three months, the y/y inflation rate “jumps” to 2.2% from the current 1.3% (see Chart 2) – hardly a five-alarm event. Then there is the opposite base effect from the runup in CPI from May to August, which will drop this August’s core CPI y/y rate back down to 1.5%.

The most important takeaway from Chart 2 is that the disinflationary trend beginning from the last month of an expansion, runs around 30 months. If the current run holds true to form, disinflation in this cycle bottoms in the second half of next year. We do not think it lasts that long because the recovery dynamics are so different, but if it did, the Fed is on course for its delayed schedule in raising policy rates. This assumes, as well, that the employment recovery follows a more typical post-recession pattern. Most, including myself and many FOMC members, expect a much more rapid recovery in re-hiring.

The most important takeaway from Chart 2 is that the disinflationary trend beginning from the last month of an expansion, runs around 30 months. If the current run holds true to form, disinflation in this cycle bottoms in the second half of next year. We do not think it lasts that long because the recovery dynamics are so different, but if it did, the Fed is on course for its delayed schedule in raising policy rates. This assumes, as well, that the employment recovery follows a more typical post-recession pattern. Most, including myself and many FOMC members, expect a much more rapid recovery in re-hiring.

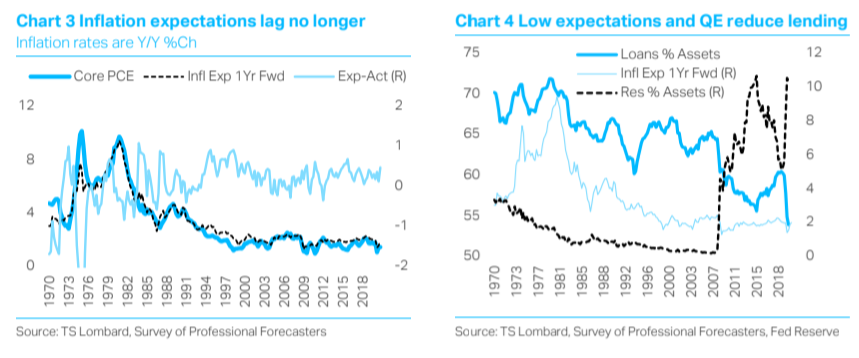

Once the recession’s impact on inflation has played out, the Fed looks to inflation expectations as kindling for the 2%+ run it is targeting. The Fed, especially Yellen, has long touted inflation expectations as a critical force – I beg to differ. Expectations do not start inflation; expectations do not stop inflation. In the 1970s, when inflation surged for many reasons global and domestic, expectations underestimated inflation (see Chart 3) and beginning in the 1980s expectations have generally overestimated inflation rates. All the while, inflation did its thing, impacted by monetary policy overshoots and, perhaps most important to the disinflationary trend, slower growth in people coming into the labour force and the sourcing of foreign labour and capital.

What the Fed is hoping for is inflating goods prices to generate borrowing for purchases and to expand production – but its policies work against this outcome. It is true that lower expectations lower lending growth, not exclusively but it is one important factor (see Chart 4). More critical is that current Fed monetary policy is not easy at all, by virtue of setting interest on reserves above short rates to grow its balance sheet. In the 1970s, this would be akin to the Fed holding down the funds rate but setting reserve requirements at 20% of deposits. The simple math for the Fed to get the inflation it wants is to set IOER below short rates until inflation rises to its target (no anticipating!) and then setting IOER equal to its target inflation rate. This, of course, means the Fed backing away from funding Treasury debt and markets repricing accordingly. As I have said, a rise in real rates from letting go Treasury debt is contractionary by itself. For the process to be “paint drying” it would have to be done over time, while the economy is expanding above trend and the budget deficit is shrinking. The Fed, in the end, has created a distortionary policy not an inflationary one. Unwinding their creation will not be easy – and a true inflationary process cannot take hold until they do so.

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact