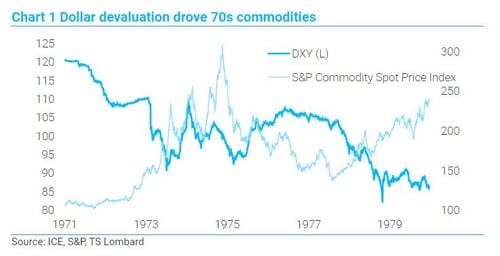

The historic analogue for current inflation does not lie in the 1970s, and the Fed’s on-again off-again response. Inflation in the 1960s eventually strained the Bretton Woods fixed-currency system to the point where it broke, and a long-needed revaluing of currencies kicked-off -- including a shock a 21% depreciation of the dollar index (DXY) in the first half of 1973. Global commodity exporters, OPEC chief among them, ramped up prices in response, and a decade long merry-go-round began (Chart 1). The Fed vacillated between tightening and easing, unsure whether to let higher oil prices slow growth and lower inflation or to inflate the economy to lower the relatively higher cost of energy.

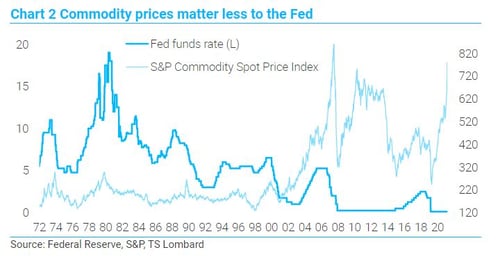

In the end, Volcker ramped up rates, returned the world to a stable dollar standard with a big US trade deficit and dollar financing globalized as a result. We are long past the days when the world complained about holding too many dollars. This combination allowed the Fed to ignore commodity prices when setting rates (Chart 2), especially in the 2000s. China’s industrialization drove up commodity prices but in return US consumers got deflating goods prices – aided and abetted by a strong dollar, despite a growing trade deficit.

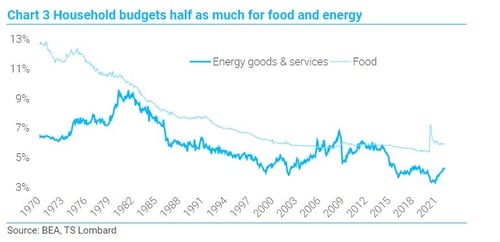

Recession risk today is lower because energy and food spending matters much less to consumers in total than it used to. In the 1970s, energy spending rose from 6% to 10% of consumer budgets while spending on food dropped from 13% to 10%. The consumption mix shifted in the 70s, but 20% of consumer spending went to food and energy goods & services regardless and today it is half that amount. A good part of the reduction in relative energy purchases owes to a more energy efficient economy. At the time of the first OPEC embargo, cars were getting about 13.5 miles/gallon compared to 25.4 today, with little difference in average miles driven per year (around 10,000). All this implies room in household budgets to reallocate to pay for higher food and energy costs, at the expense of a small shift in spending on other, discretionary items. Higher commodity prices will slow overall spending but not tip the economy into recession (it did not in the past either, the Fed did it!). Further, the inventory and debt overhangs that are preconditions for recession are absent.

Recession risk today is lower because energy and food spending matters much less to consumers in total than it used to. In the 1970s, energy spending rose from 6% to 10% of consumer budgets while spending on food dropped from 13% to 10%. The consumption mix shifted in the 70s, but 20% of consumer spending went to food and energy goods & services regardless and today it is half that amount. A good part of the reduction in relative energy purchases owes to a more energy efficient economy. At the time of the first OPEC embargo, cars were getting about 13.5 miles/gallon compared to 25.4 today, with little difference in average miles driven per year (around 10,000). All this implies room in household budgets to reallocate to pay for higher food and energy costs, at the expense of a small shift in spending on other, discretionary items. Higher commodity prices will slow overall spending but not tip the economy into recession (it did not in the past either, the Fed did it!). Further, the inventory and debt overhangs that are preconditions for recession are absent.

The funds rate rises, there is no question on this score, the question is how much, how fast, and how aggressively to counter the inflationary impact of higher commodity prices. The Fed will tack a slow, cautious course to 2.5% set against the winds of equity market volatility, believing this is the best course as higher prices slow the economy on their own accord. If, however, slow drops earnings estimates enough, the equity market tells the Fed to stop, and the Fed will stop. At the moment, market pricing is generally expecting no recession with the Fed getting to 2.5% in 18 to 24 months (not sooner which would hike the 2Y and invert the curve) with a terminal inflation rate in the 2.5%-3.0% range. As I have written many times before, the Fed will accept this inflation outcome and embrace it in August when Powell gives his speech at Jackson Hole.

Growth slows, inflation follows, but the inflation story does not end here. This is not the 70s, when dollar depreciation put commodity producers in constant catch-up mode on prices. With the dollar still stable-to-strong, higher prices for commodities will generate a supply response (nickel will be found, more aluminium will be produced, etc) and stagflation is avoided -- unless foreign sources of production turn unresponsive or shrink. It is fair to say current tectonic political shifts mark the end of the “long peace” (1989-2019) and what comes in its stead will reshape economic activity for the coming generation. The Fed will no longer have the luxury of expanding global sources of production to put downward pressure on domestic goods prices and, in turn, wages. Reshoring does not mean stagflation, but it does alter domestic dynamics, to the better for many. It also raises the potential for a credit cycle to replace the asset cycle the Fed created for the past decade – just when a massive amount of excess reserves begins to be returned to the banks.

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact