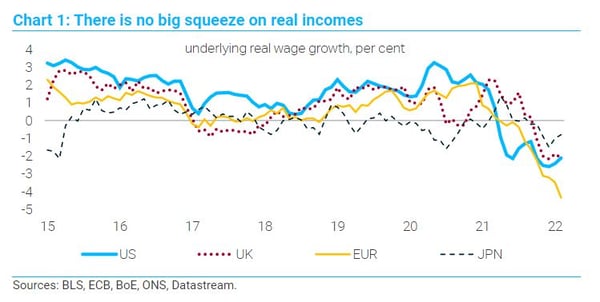

There is currently a big debate about whether central banks will need to generate a recession in order to force inflation lower. For the doves, such action is not necessary – because the “cure for high prices is high prices”. And this (sort of) makes sense: with wages failing to keep pace with prices, consumers all over the world are already facing a massive squeeze on their real incomes (Chart 1). Yet, not everyone agrees. As the once uber-dovish Adam Posen put it in a recent FT article: “If declines in real incomes drove inflation cycles, we wouldn’t need monetary policy. The whole reason you need policy-induced recessions is that real income doesn’t reduce inflation unless labour-market conditions ease.” With transitory explanations of inflation now clearly out of fashion, Posen’s analysis leads us to a very gloomy conclusion: a recession may now be inevitable, perhaps even “necessary”. And while the last few months have been painful for risk assets, there is no way a recessionary outcome is currently priced in. So far, in fact, the hawkishness of central banks has merely deflated the “COVID asset-price bubble”.

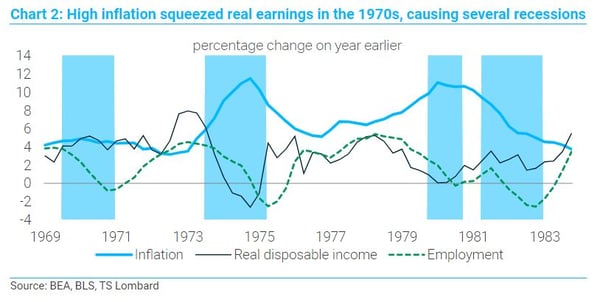

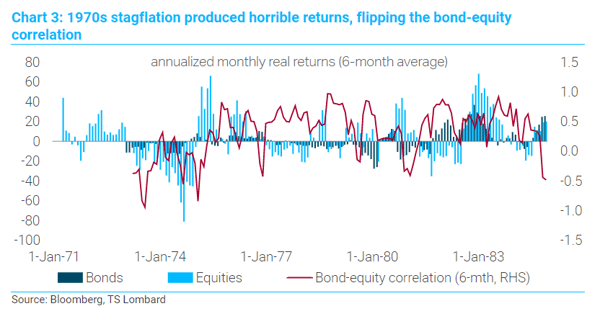

There is an underlying question here that is extremely important for investors. If inflation is the cause of an economic slowdown (via its impact on real incomes), will the resulting deterioration in the economy do anything to resolve inflation itself? The lesson from the 1970s is not encouraging. The US, for example, suffered three recessions during that decade, with each downturn the result of a large spike in commodity prices, which killed real incomes. But the underlying inflation problem never went away. Prices slowed during each downturn – as the commodity shock faded – but then reaccelerated, typically on a faster trend than before the recession. And this continued until central banks – most notably the Volcker Fed – engineered their own recession, raising interest rates sufficiently to put millions of people out of work. In the 1970s, it eventually took extremely tight policy and mass unemployment to “break the back of inflation”. From an investor point of view, this was the worst of all worlds – countercyclical inflation (stagflation) that produced a persistent positive correlation between bond and equity returns.

There is an underlying question here that is extremely important for investors. If inflation is the cause of an economic slowdown (via its impact on real incomes), will the resulting deterioration in the economy do anything to resolve inflation itself? The lesson from the 1970s is not encouraging. The US, for example, suffered three recessions during that decade, with each downturn the result of a large spike in commodity prices, which killed real incomes. But the underlying inflation problem never went away. Prices slowed during each downturn – as the commodity shock faded – but then reaccelerated, typically on a faster trend than before the recession. And this continued until central banks – most notably the Volcker Fed – engineered their own recession, raising interest rates sufficiently to put millions of people out of work. In the 1970s, it eventually took extremely tight policy and mass unemployment to “break the back of inflation”. From an investor point of view, this was the worst of all worlds – countercyclical inflation (stagflation) that produced a persistent positive correlation between bond and equity returns.

So why didn’t the 1970s recessions “cure” inflation? First, each downturn was relatively short-lived. Sudden price spikes cut spending power, but then real incomes bounced back. In today’s context, this is (sort of) good news because it points to a soft patch rather than a deep slump. The second reason the recessions of the 1970s did not alleviate inflation is that workers secured higher wages even as the economy deteriorated. This effectively replaced one source of cost-push inflation (commodities) with another (labour). The whole episode is synonymous with “wage-price spirals”, essentially a power struggle between labour and capital. Productivity declined and society spent the next decade trying to figure out who should bear the burden of this adjustment, until neoliberalism (Thatcherism, Reaganomics, etc.) provided a definitive answer – by crushing worker power. Up to that point, a young militant workforce was able to resist any sustained real-wage squeeze. And, at least for a period in the late 1970s, the private sector borrowed heavily and reduced its saving, which also delayed the moment of pain.

What does this mean today? Households and businesses can respond to the CPI shock in three ways:

- Spend the same in nominal terms and accept a reduction in real spending. The economy will slow, perhaps even contract, but things will improve once costs stabilize (though there is always a risk of “non-linear” effects, especially if unemployment increases and you get further rounds of contraction);

- Reduce savings, or borrow more, to preserve real spending power. This will limit the hit to the economy and inflation should eventually subside. But people cannot sustain this for long;

- Resist the squeeze by demanding higher wages. Real GDP and employment will remain resilient, but the inflation problem lingers, probably at levels that are inconsistent with central banks’ targets.

Central banks are obsessed with the third of these scenarios, which is why they are watching wages especially closely. While a 1970s-style wage-price spiral does not seem very likely – basically because our governments have spent the last 40 years dismantling the institutions that produced those dynamics – policymakers are clearly worried about the tightness they are seeing in labour markets. The threat that wages could produce a more persistent inflation overshoot seems much greater in the US (and, to a lesser extent, the UK) than in the euro area and Japan. But in all jurisdictions, it is clear that the ghosts of the 1970s are causing central banks to constantly ratchet up their hawkishness, regardless of what is happening to economic growth. Naturally, this is creating a really difficult environment for financial markets. Leading indicators are set to deteriorate, perhaps sharply, but inflation anxiety will linger, which means we are a long way from any dovish pivot from central banks. Even if this is not “the end of the cycle” – that comes later if inflation fails to settle at tolerable levels – the next few months could be ugly.

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact