The Fed’s problem is that current price hikes from shortages of goods and labour will pass, but the coming increase in wages will not. Because the conduit of monetary policy runs through the dollar and the equity markets, the Fed is left with trying to take down current inflation with a higher funds rate boosting the dollar that lowers import prices (the “secret sauce” of low inflation for a generation) -- and hope wage growth cools along the way. Failing that, their only lever left is raising real term yields to pull down the equity market – a policy direction not in their playbook.

Fed policy and the banks no longer operate in a world where a higher funds rate slows borrowing as banks pass through their higher cost of funding – a higher funds rate now boosts bank earnings. Further, current inflation has been created by supply chain problems and a demand surge for goods created by a confluence of factors that boosted household balance sheets, notably fiscal transfers, and a too strong equity market from the Fed doing too much – but not outsized leverage to fund purchases. This leaves yields-restricting-borrowing a lost lever to slow the current pace of inflation.

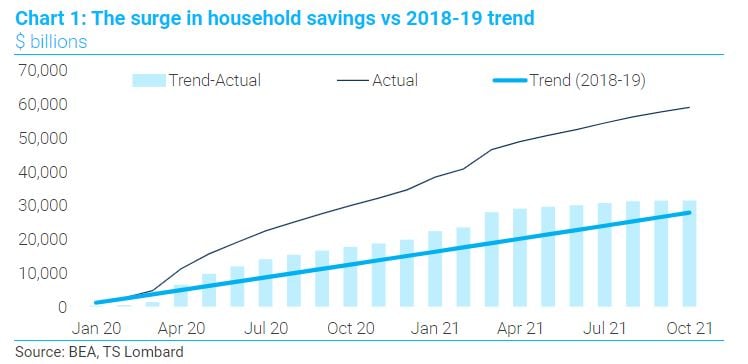

Current supply side issues eventually sort themselves, and price increases have already begun to soften, this leaves household balances and wage increases as the inflation “threat”. The coming cyclical inflation story begins with the volume of savings sitting on household balance sheets, more than enough to counter inflation reducing purchasing power. Looking at the cumulative sum of saving in the past 22 months versus the sum had the 2018-19 trend line continued, savings are about $28trn above trend (Chart 1) – without accounting for any capital changes from investments. The spread to trend has stabilized of late, with the saving rate naturally coming down as fiscal transfers drop with programs ending and employment improving. On the other hand, the Biden “Build Back Better” bill now in the Senate offers a new round of credits to middle and lower income earners for the coming years, at the cost of raising taxes on high earners and corporations. To be clear, far from all these savings will be spent down in the next year or two – baby boomers were under-saved for retirement when the Covid-crisis hit, and the hallmark of an aging population is higher savings and less leverage.

Wage growth, to date, has disproportionately gone to workers in short supply, concentrated in the lower two quartiles of wage earners (Chart 2). Given how this group was hit with downward mobility in the past decade and saw their balance sheets gain debt as a result, there should little surprise that a strong bid for goods has emerged as savings surged. Current demand for goods is not only about a lack of services on which to spend money, or the shift in lifestyle to remote work environment– boosting demand for cars and household goods.

Wage growth, to date, has disproportionately gone to workers in short supply, concentrated in the lower two quartiles of wage earners (Chart 2). Given how this group was hit with downward mobility in the past decade and saw their balance sheets gain debt as a result, there should little surprise that a strong bid for goods has emerged as savings surged. Current demand for goods is not only about a lack of services on which to spend money, or the shift in lifestyle to remote work environment– boosting demand for cars and household goods.

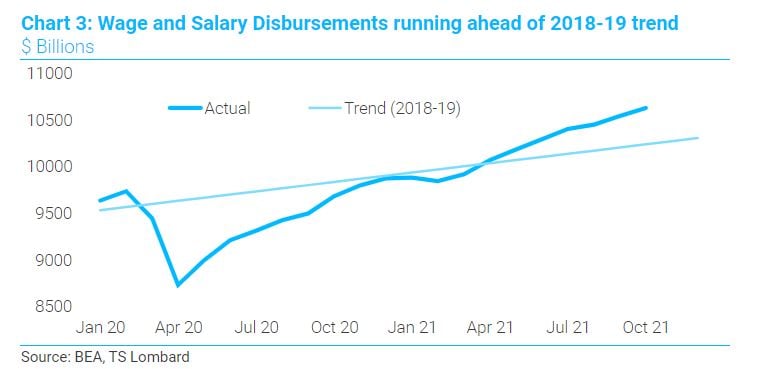

Eventually, current spending drops back to trend in wages and employment, but in 2022, wage gains should broaden based on strong earnings in 2021 and put in place a steeper trend. We already see a glimmer of this with wage and salary disbursements (product of wages and employment) now running ahead of its 2018-19 trend line (Chart 3). While the wage dynamics about to get underway will reflect current inflation, 2021 earnings, and tight labour markets (as Powell noted in his testimony) there are other, longer-run factors that will give the coming cycle a higher trajectory for wage growth. Among them is a mix-shift of hiring into mid-skill mid-income jobs from the low-skill low-wage jobs that dominated the prior cycle. In addition, there will be an underlying upward bias for real wages because Gen Z, now entering the work force, is a smaller population cohort than Millennials.

Eventually, current spending drops back to trend in wages and employment, but in 2022, wage gains should broaden based on strong earnings in 2021 and put in place a steeper trend. We already see a glimmer of this with wage and salary disbursements (product of wages and employment) now running ahead of its 2018-19 trend line (Chart 3). While the wage dynamics about to get underway will reflect current inflation, 2021 earnings, and tight labour markets (as Powell noted in his testimony) there are other, longer-run factors that will give the coming cycle a higher trajectory for wage growth. Among them is a mix-shift of hiring into mid-skill mid-income jobs from the low-skill low-wage jobs that dominated the prior cycle. In addition, there will be an underlying upward bias for real wages because Gen Z, now entering the work force, is a smaller population cohort than Millennials.

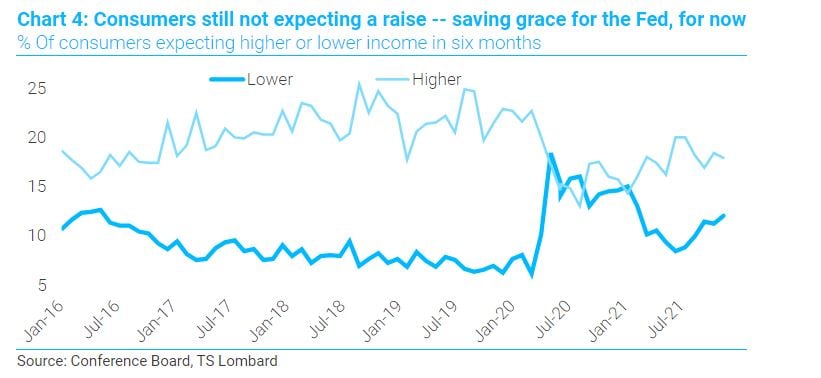

Interestingly, consumers do not yet see this positive wage outlook for themselves. The November Conference Board Survey showed that the percentage of consumers expecting higher income in six months dipped and it remains well below pre-Covid levels (Chart 4). In addition, the percentage expecting lower income has increased and is well above pre-Covid levels. This. for now, is a saving grace for the Fed because inflationary processes are financed and therefore need household and business to have strong expectations for higher income. With the consumer outlook for income still low, it is no surprise that borrowing to spend has not been behind the current price increases. Consumer borrowing has picked up of late, but only in line with growth in current income.

Interestingly, consumers do not yet see this positive wage outlook for themselves. The November Conference Board Survey showed that the percentage of consumers expecting higher income in six months dipped and it remains well below pre-Covid levels (Chart 4). In addition, the percentage expecting lower income has increased and is well above pre-Covid levels. This. for now, is a saving grace for the Fed because inflationary processes are financed and therefore need household and business to have strong expectations for higher income. With the consumer outlook for income still low, it is no surprise that borrowing to spend has not been behind the current price increases. Consumer borrowing has picked up of late, but only in line with growth in current income.

In sum, the Fed in 2022 could be facing a Hobson’s Choice of its own design because the current structure of monetary policy is ill suited to deal with today’s problems. They could ramp up the dollar further, but the negative impact on the tradeable goods and service sectors of the economy runs counter to what the Administration is trying to achieve. Longer-run disinflationary forces are still in play, namely the aging population, technology replacing labour at a faster pace, and the lingering effect of Covid on re-employment in services the virus has curtailed – notably leisure and hospitality. While these factors, among others, will keep inflation from soaring, they do not, in the intermediate term, get current inflation back running steadily below 3%. To get there, the Fed will need to act. AIT was a promise to not raise rates too soon, not a promise to keep real rates falling as a recovery takes hold.. This is where policy today is lagging, and it is questionable whether a dollar-strengthening strategy alone will prove sufficient. The equity market is consequently the lever left if the dollar and other forces (domestic disinflationary forces, disinflation from China, unwinding of supply constraints) fail to quell current inflation. We think this combination of forces will lower inflation enough in the coming year to keep the Fed from using term yields to lower the equity market – but that risk does exist. That risk should, more to our point, create some reckoning at the Fed regarding their policy positioning for the world to come. Even if inflation comes off the boil in the coming year, as we expect, the economy is nevertheless set for a higher inflation profile than it has had in a generation, 2.5%-3.0% is our reckoning.

In sum, the Fed in 2022 could be facing a Hobson’s Choice of its own design because the current structure of monetary policy is ill suited to deal with today’s problems. They could ramp up the dollar further, but the negative impact on the tradeable goods and service sectors of the economy runs counter to what the Administration is trying to achieve. Longer-run disinflationary forces are still in play, namely the aging population, technology replacing labour at a faster pace, and the lingering effect of Covid on re-employment in services the virus has curtailed – notably leisure and hospitality. While these factors, among others, will keep inflation from soaring, they do not, in the intermediate term, get current inflation back running steadily below 3%. To get there, the Fed will need to act. AIT was a promise to not raise rates too soon, not a promise to keep real rates falling as a recovery takes hold.. This is where policy today is lagging, and it is questionable whether a dollar-strengthening strategy alone will prove sufficient. The equity market is consequently the lever left if the dollar and other forces (domestic disinflationary forces, disinflation from China, unwinding of supply constraints) fail to quell current inflation. We think this combination of forces will lower inflation enough in the coming year to keep the Fed from using term yields to lower the equity market – but that risk does exist. That risk should, more to our point, create some reckoning at the Fed regarding their policy positioning for the world to come. Even if inflation comes off the boil in the coming year, as we expect, the economy is nevertheless set for a higher inflation profile than it has had in a generation, 2.5%-3.0% is our reckoning.

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact