March will mark the first Fed rate hike, sooner than the June timing I recently shifted to, and much sooner than the original Q4 call made in November 2020. The timing is being pulled forward because the circumstances for starting a rate hike cycle that were anticipated a year ago are onrushing with unanticipated speed. AIT was a promise to not raise rates too soon, not a promise to keep real rates falling as a recovery takes hold. To be clear, our call is not about the current shortage-related price spikes. It is about an inflationary process (wages and, soon enough, borrowing) taking hold and the FOMC belatedly recognizing they need to catch up.

Compounding the difficulty of their task is the messy truth that the Fed’s impact comes through asset markets first, and the main market, equities, is one they intend to protect. This leaves them trying to slow momentum with a stronger dollar – a less effective tool in current circumstances that also comes with a political limit, namely the negative impact on tradeable goods and services. This runs counter to what the Biden administration is trying to achieve. Remember too, all this will be playing out with the mid-term election on the horizon.

Markets are priced 65/35 against a March hike, but once they come around to pricing one in, four hikes will get priced into 2022. Pushing the funds rate up above 1% in a year’s time still leaves the real rate cheap, given current levels of economic activity -- even if inflation drops back under 3%. The market coming to price in four hikes in 2022 is rational based on recent history but projecting that this rate cycle will look like the ones that have come before is a fool’s errand. The prospect for ever more virus variants disrupting activity (jury is still out on Omicron’s impact), the property-problems in China, and the unwinding of current supply bottlenecks, are likely to deliver the second half 2022 deflation greater than what the Fed expects and may very well keep them from hiking more than twice in 2022.

On the other hand, and there is always more than one, these downside risks could fall away, prove less traumatic than feared, and instead leave the Fed with an inflation problem rooted in banks “getting back” reserves that need to be invested against a backdrop of broadly rising wages, notably for the lower income brackets, improving productivity – enough to incentivize capex – and increased government spending on infrastructure. The downward shift in who gets the better income growth will sustain goods buying, rather than boost spending on leisure, savings and, in turn, inflows into capital markets. Critically, the dollar will eventually prove a poor limiter of these forces, thus leaving the Fed with managing the impact of their balance sheet on term yields against acceptable downside risk for the equity market. A complete business cycle of the Fed’s very own could be in the making.

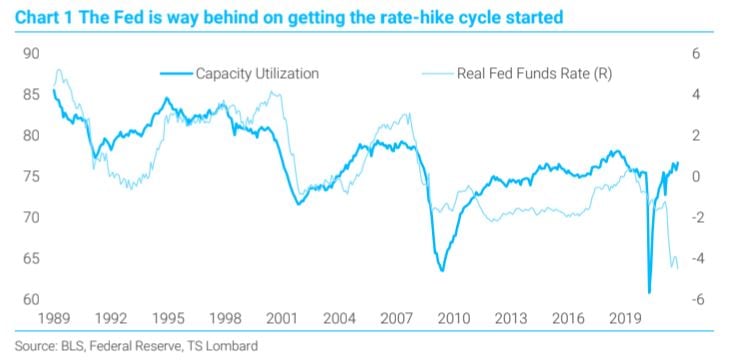

Industrial capacity utilization remains the best guidepost for signalling Fed rate cycles, even though the service sector is economically more important. From this perspective, the Fed is way behind prior tightening cycles. The last cycle ended with the real funds rate topping out at around 35bps, and chances of the Fed reaching this level within a year are slim and none. Just getting the real funds rate back to -1.75%, its 2012-16 average when capacity was averaging75.2% (currently 76.7%) requires a 1% nominal funds rate and Y/Y core CPI inflation dropping back below 3% from its current 4.6% pace. If all goes well, this could be the math by the end of next year. Even then, policy would hardly be considered tight with demand still growing apace and wage increases accelerating. If the quashing of domestic inflation does not come from the world, the Fed could see itself pressured to slow equities instead – a Hobson’s Choice if there ever was one, and one of their own makings. Productivity eventually plays a positive role in this cycle, offsetting some of the Fed’s potentially more difficult choices, but this is unlikely to be overly evident in the near term.

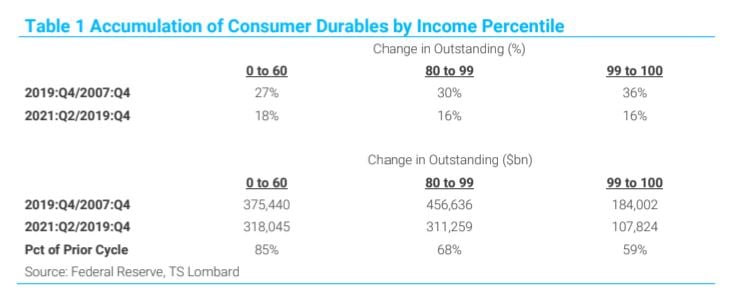

Rather than write again on employment being full enough for the Fed to have acted, and the coming wage cycle, the surge in goods demand bears examination. The market narrative is that people stuck at home bought a couch because they couldn’t eat dinner out. That makes for good reading, but data reveal the fallacy of this argument – and lays out a roadmap for continued strength in goods purchases during this cycle. Table 1 illustrates that the accumulation of consumer durables was more rapid among those in the 0-to-60 percentiles for income since 2019:Q4 – they were the lowest accumulators from 2007:Q4 to 2019:Q4. The pace of accumulation in these most recent quarters was 85% of the prior cycle. In contrast, the percentage for the next highest brackets was 68% and 59%, respectively. This occurred because the thrust of Covid fiscal policies benefitted the bottom income percentiles most, and the proposed Build-Back-America legislation is similarly focused, although the numbers are smaller. In addition, Trump’s tax and tariff policies, Covid redirecting supply chains back to the US (highest job openings/hiring ratio is in manufacturing) and the recently passed infrastructure program will favour workers that were faced with downward mobility in the past decade – specifically those in manufacturing and construction.

Rather than write again on employment being full enough for the Fed to have acted, and the coming wage cycle, the surge in goods demand bears examination. The market narrative is that people stuck at home bought a couch because they couldn’t eat dinner out. That makes for good reading, but data reveal the fallacy of this argument – and lays out a roadmap for continued strength in goods purchases during this cycle. Table 1 illustrates that the accumulation of consumer durables was more rapid among those in the 0-to-60 percentiles for income since 2019:Q4 – they were the lowest accumulators from 2007:Q4 to 2019:Q4. The pace of accumulation in these most recent quarters was 85% of the prior cycle. In contrast, the percentage for the next highest brackets was 68% and 59%, respectively. This occurred because the thrust of Covid fiscal policies benefitted the bottom income percentiles most, and the proposed Build-Back-America legislation is similarly focused, although the numbers are smaller. In addition, Trump’s tax and tariff policies, Covid redirecting supply chains back to the US (highest job openings/hiring ratio is in manufacturing) and the recently passed infrastructure program will favour workers that were faced with downward mobility in the past decade – specifically those in manufacturing and construction.

In sum, the on rush of the economy’s return to normal and then some (recovering income for the lower percentiles) has pulled forward the timing of the Fed’s first hike to March. Once the markets embrace that timing, they will also price in four hikes for 2022. While sympathetic to that view considering recent history and how far behind the Fed is in this cycle (AIT is in force!), there is also a large probability that the deflation the Fed anticipates arrives in the second half of 2022 and is even greater than what the Fed expects. If that occurs, and we think it has a high probability, four hikes in 2022 is not a reality. On the other hand, if it does not occur, the Fed has a lot of catching up to do, with the problem that the impact of its policy tools is limited to asset markets first, rather than lending. Perhaps the best way to see the coming rate cycle is to recognize that it will prove out to be unlike any of recent memory. For now, first hike in March, and then we will see how the world, and the virus, are behaving.

In sum, the on rush of the economy’s return to normal and then some (recovering income for the lower percentiles) has pulled forward the timing of the Fed’s first hike to March. Once the markets embrace that timing, they will also price in four hikes for 2022. While sympathetic to that view considering recent history and how far behind the Fed is in this cycle (AIT is in force!), there is also a large probability that the deflation the Fed anticipates arrives in the second half of 2022 and is even greater than what the Fed expects. If that occurs, and we think it has a high probability, four hikes in 2022 is not a reality. On the other hand, if it does not occur, the Fed has a lot of catching up to do, with the problem that the impact of its policy tools is limited to asset markets first, rather than lending. Perhaps the best way to see the coming rate cycle is to recognize that it will prove out to be unlike any of recent memory. For now, first hike in March, and then we will see how the world, and the virus, are behaving.

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact