Every investor wants to know whether central banks are prepared to cause a recession in order to force inflation down. Surely, officials are bluffing, right? But think about it from the central banker’s perspective. Yes, a recession would be bad: people would lose their jobs, and it could take a while to recover. But recessions happen all the time and they rarely ruin any central banker’s reputation. Some, such as Paul Volcker, are even celebrated for their “toughness” in the face of economic pain. And if a recession happens now, the authorities can blame Putin or say it was the only way to tame the inflation monster (they love a good counterfactual). Runaway inflation, on the other hand, would leave a darker legacy. Jerome Powell, Christine Lagarde and others would be joining Arthur Burns on university syllabuses for the semester on “historical monetary failures”. In 40 years’ time, economists would still be discussing how they “let IT (the 1970s) happen again”. No central banker wants to become a case-study in how to fail.

When I tweeted about the distorted personal incentives central bankers face, someone replied: "Is this what monetary policy has become? A silly [legacy-] covering exercise?” (he used different, less polite wording). Partly yes. Officials feel utterly embarrassed about their “transitory” call in 2021, and you should never ignore the human element in policymaking. But the new bias goes deeper than that. It is also important to remember that the reason we have independent central banks is to ensure that the 1970s cannot happen again. So, we are talking about a risk that undermines the central bankers’ entire raison d'être, an existential threat. In fact, “price stability" is a prerequisite for everything else they do. It is the foundation of monetary policy. When investors ask about the pain central banks are prepared to tolerate, they are thinking about the wrong trade-off. The authorities are prepared to suffer a recession now because they fear a much worse recession in the future if price stability is lost. The trade-off, as officials see it, is intertemporal.

When I tweeted about the distorted personal incentives central bankers face, someone replied: "Is this what monetary policy has become? A silly [legacy-] covering exercise?” (he used different, less polite wording). Partly yes. Officials feel utterly embarrassed about their “transitory” call in 2021, and you should never ignore the human element in policymaking. But the new bias goes deeper than that. It is also important to remember that the reason we have independent central banks is to ensure that the 1970s cannot happen again. So, we are talking about a risk that undermines the central bankers’ entire raison d'être, an existential threat. In fact, “price stability" is a prerequisite for everything else they do. It is the foundation of monetary policy. When investors ask about the pain central banks are prepared to tolerate, they are thinking about the wrong trade-off. The authorities are prepared to suffer a recession now because they fear a much worse recession in the future if price stability is lost. The trade-off, as officials see it, is intertemporal.

A recent report from the BIS outlines the nightmare scenario for central banks. For a long time, BIS analysis has not been useful for analysing monetary policy. The Basel-based “central bankers’ central bank” was obsessed with publishing endless critiques of ZIRP, QE and other “unconventional stimulus”, a message that clearly did not resonate with the view at the top of the Fed, the ECB or the majority of officials who were actively involved in policy decisions. But the BIS’s latest report on the danger of a “new paradigm” in global inflation clearly strikes at central bankers’ worst fears. It explains, clearly and with lots of fabulous charts, why the authorities are suddenly more hawkish than anyone could have imagined 12 months ago – why Jerome Powell is suddenly celebrating Paul Volckers’ legacy, and why the ECB and even the BoE now have a rather bizarre obsession with the monetary traditions and “credibility” of the Bundesbank.

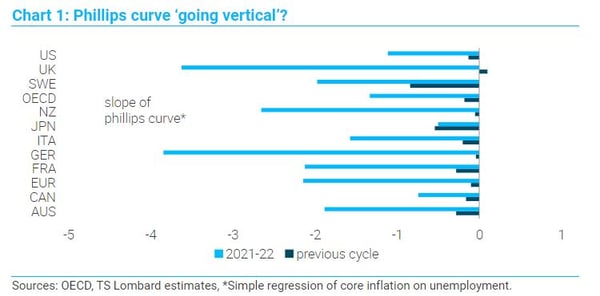

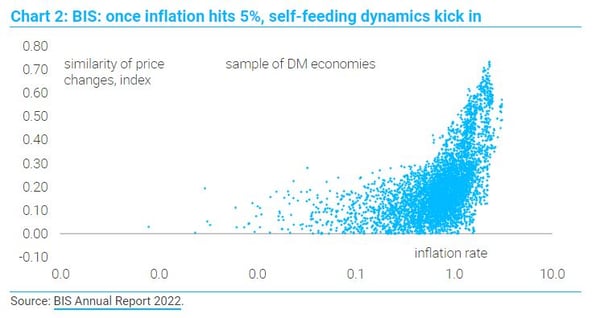

The BIS analysis is largely statistical. It argues that there are two basic inflation regimes – “low” and “high”, each of which has its own self-reinforcing properties, although economies occasionally transition from one to the other. In the low-inflation regime, “relative” or sector-specific price changes are the dominant driver of the CPI. These tend to have a transitory effect, as they die out quickly. This is not a regime in which wage- or price-setters need to pay a great deal of attention to the overall inflation rate. Aggregate price pressures are subdued, and everyone takes this for granted. In the “high-inflation regime”, on the other hand, broader CPI developments start to have a much more discernible impact, with inflation itself becoming the focal point for private-sector decisions. This shift in emphasis leads, in turn, to behavioural changes that will cause inflation to become entrenched. In the high-inflation regime, even relative price shifts – such as spikes in energy prices – have persistent effects. And you know transitioning from a low inflation regime to a high inflation regime is under way based on the behaviour of prices within the CPI. Once they become more correlated, as they have over the past 12 months, there is a good chance – according to the BIS – that the economy is transitioning.

Of course, it is easy to pick holes in the BIS analysis. Their high-inflation regime is exclusively a description of what happened in the 1970s, the only period in history where consumer prices behaved in this way. As we have explained elsewhere, the Great Inflation was a power struggle between labour and capital, which is not likely to happen again anytime soon. After 40 years of neoliberalism, the basic structure of the economy is radically different today. This is why we do not find the wage-price spiral, which is an important propagation mechanism in the BIS analysis, convincing (as I have explained previously). And the broadening of inflation pressures since 2021 could be pass-through from unprecedented supply shocks and cost pressures, rather than evidence of “de-anchoring”. Higher and broader inflation is not necessarily “persistent”. But it does not matter what we believe – it is clear that the BIS message resonates with central banks. They believe monetary policy is what “anchors” the low-inflation regime and if the authorities lose control, the “costs of transitioning away from the high-inflation regime would be extreme”.

Of course, it is easy to pick holes in the BIS analysis. Their high-inflation regime is exclusively a description of what happened in the 1970s, the only period in history where consumer prices behaved in this way. As we have explained elsewhere, the Great Inflation was a power struggle between labour and capital, which is not likely to happen again anytime soon. After 40 years of neoliberalism, the basic structure of the economy is radically different today. This is why we do not find the wage-price spiral, which is an important propagation mechanism in the BIS analysis, convincing (as I have explained previously). And the broadening of inflation pressures since 2021 could be pass-through from unprecedented supply shocks and cost pressures, rather than evidence of “de-anchoring”. Higher and broader inflation is not necessarily “persistent”. But it does not matter what we believe – it is clear that the BIS message resonates with central banks. They believe monetary policy is what “anchors” the low-inflation regime and if the authorities lose control, the “costs of transitioning away from the high-inflation regime would be extreme”.

Rather ominously for financial markets, the BIS concludes: “Central banks fully understand that the long-term benefits [of safeguarding price stability] far outweigh any short-term costs – credibility is too precious an asset to be put at risk.” This suggests that a policy pivot is far away…

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact