The bounce in global stock markets since March has been both spectacular and a bit puzzling. Despite widespread gloom among institutional investors about ‘fundamentals’ – concerning both the macro outlook and the likelihood of a ‘second wave’ of COVID-19 infections – US equities have returned to where they traded in December. And back then, everyone thought 2020 would be an incredibly dull year where Goldilocks would continue to shape macro/market outcomes (i.e. not a year of deadly pandemics, mass layoffs and the biggest declines in GDP since 1709). Of course, pundits have tried to back-fit various narratives to this rally, including TINA (“There Is No Alternative” to stocks at zero bond yields), FOMO (“Fear of Missing Out”, especially among new Robinhood investors) and even the odd conspiracy theory. Since most of the rally happened outside regular trading hours, perhaps a foreign power was trying to influence the US election1. But one game has been more popular than the others – blaming central banks.

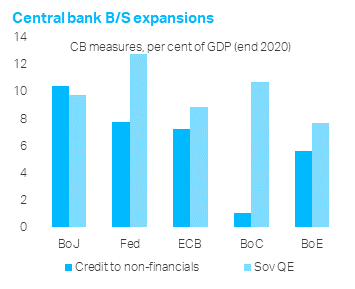

There is no doubt central banks, especially the Fed, averted a financial crash in March. Systemic vulnerabilities – particularly the dollar shortage and the global search for yield among institutional investors – were creating a gigantic run on the shadow banking system (or the ‘market-based system of credit provision’, as officials call it). But policymakers stepped in, providing a backstop to global markets and a lender-of-last-resort to the corporate sector, which faced a massive cash-flow crisis. To the extent financial markets were beginning to price-in the tail risk of a severe financial collapse, it makes sense that asset prices would bounce from their March lows and financial conditions would improve. Learning the lessons from 2008, and with an enhanced understanding of macro-financial spillovers/risks, policymakers prevented a repeat catastrophe.

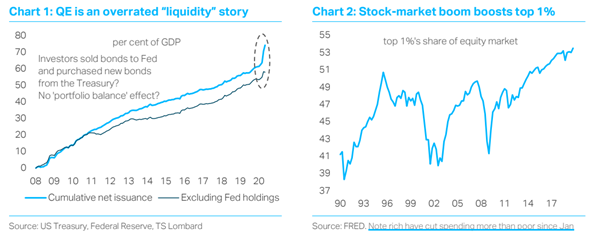

Yet despite their success in March, it is pushing this newfound confidence in policymakers too far to believe official “liquidity” must keep asset prices high, or that there is now a fool-proof central bank “put” that has effectively made risk assets “riskless”. For a start, it is important to remember that policymakers don’t care if investors lose money per se. Protecting the wealthy is not part of their mandate. Even in the US, where equity ownership is more widespread than in other developed economies, the top 1% hold the vast majority of stocks. We know that the Federal Reserve traditionally responds to stock market declines – there is even academic evidence to supports this thesis – but officials only care about financial markets to the extent they influence the real economy. Would, say, a quick 20% plunge in the stock market, after the powerful rally since March, definitely force central banks to respond? Remember, officials are already expecting a grim macro outlook. And the speed of the rally – happening alongside mass unemployment – has been a public-relations disaster for many officials

So, even if you believe in the power of the central-bank “put”, equities cannot be risk-free because the objectives of investors and policymakers are not always perfectly aligned. But there is a deeper problem. There is plenty of evidence to show monetary policy is becoming less effective at stimulating the macro economy, which means the ultimate potency of the policy “put” is questionable. Financial markets cannot diverge from macro fundamentals indefinitely. It might have felt like they did over the past decade – a subdued macro environment where there were always plenty of pundits warning about the “disconnect” between Wall Street and Main Street – but this was largely a story of asset prices “rerating” on the basis of declining long-term interest rates. There is no evidence, contrary to what the perma-bears have claimed, that central bank “liquidity” or various QE programmes systematically distorted bond markets and produced “artificially” low bond yields2. A decade of low interest rates shows something more profound was happening. And we shouldn’t assume this latest rally is just a continuation of the secular stagnation rerating. Yes interest rates will stay low, but future earnings could be disastrous.

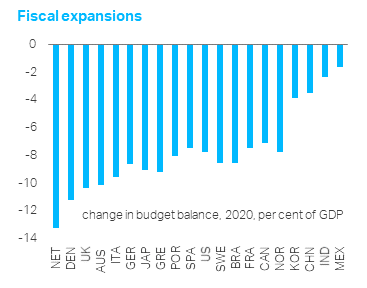

Unfortunately, we suspect the 40% bounce in US stocks since March will turn out to be a particularly powerful – though not unprecedented – “Bear Market Rally”. During every major downturn there is always a phase, typically early in the recession, where policymakers start to respond and financial markets recover – albeit temporarily – on the basis that the authorities understand the severity of the situation and will act decisively to avert it. Back in 2008, for example, many investors believed even modest interest-rate cuts would quickly transform the global outlook. Of course, this latest bear-market bounce has been sharper than most previous vintages, but then it followed a steeper decline in stocks and has elicited more aggressive policy action. Yet history shows there is still a boom-bust cycle and policymakers are never fully in control, even if they sometimes give the impression they are. The important question is whether officials have done enough to return the global economy to its pre-pandemic trajectory. We think they haven’t and that ultimately a large, multi-year fiscal expansion will be necessary, not just zero yields and endless rounds of QE. Until then, any global policy “put” is incomplete.

1 Actually this “Overnight Drift” was well documented even before COVID-19 and probably reflects the fact that most corporate earnings reports and macro data happen outside US trading hours

2 A more sensible version of this story is that the mix of monetary and fiscal policy was all wrong, - which we have written about in detail – but the main problem was on the budgetary side. Tighter monetary policy wouldn’t have lifted yields

Client Login

Client Login Contact

Contact